Attachment theory, developed by psychologists John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, provides insights into how individuals form and maintain relationships with others. Anxious and avoidant attachment styles are two primary attachment styles identified in attachment theory.

Attachment avoidance describes the degree to which people are comfortable with intimacy and dependence on others. Attachment anxiety reflects the degree to which people fear being abandoned, rejected, and underappreciated by their significant others.

Individuals with avoidant attachment are characterized by a high level of attachment avoidance. They often have difficulty with emotional intimacy and prioritize their independence.

They are reserved when it comes to sharing their emotions and vulnerabilities. They tend to have a strong desire to maintain their personal space and may become uncomfortable when others get too close.

Individuals with anxious attachment tend to have a high level of attachment anxiety. These individuals often desire constant closeness and intimacy in relationships and may struggle with any perceived emotional distance.

People with anxious attachment styles tend to express their emotions more openly and intensely. They will frequently seek reassurance and validation from their partners and may become distressed when their needs for attention and affection are not met.

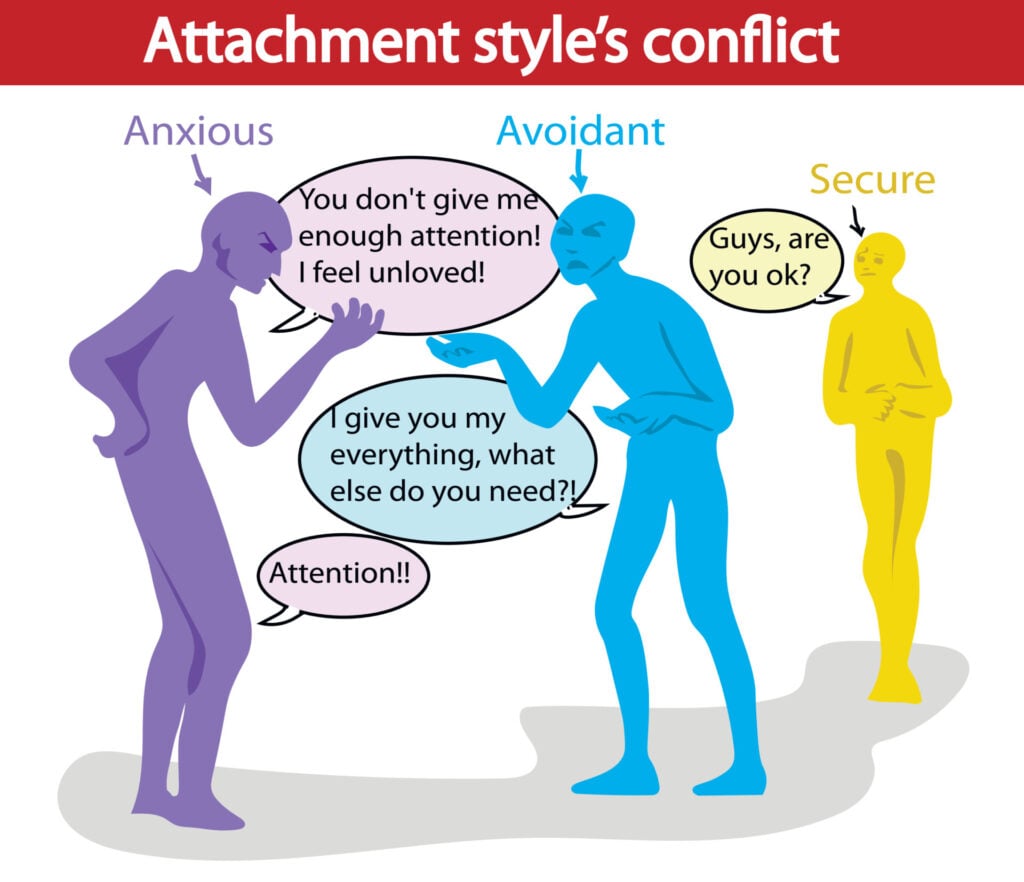

Differences Between Anxious & Avoidant Attachment

Anxious and avoidant attachment styles are distinct patterns of relating to others in close relationships.

Both anxious and avoidant attachment styles are considered insecure attachment style because they involve feelings of insecurity, discomfort, or anxiety in relationships.

However, the way this fear is expressed in each attachment style is significantly different.

While this article will discuss attachment styles in terms of their standard definitions and typical behaviors, it’s important to note that these are not rigid categories, and individuals may exhibit a combination of anxious and avoidant tendencies to varying degrees.

Here are some key differences between anxious and avoidant attachment styles:

Approach to Closeness and Intimacy

Individuals with an anxious attachment style tend to desire and seek a high level of emotional closeness and intimacy in their relationships. They often worry about their partner’s availability and may feel insecure if they perceive any emotional distance.

They are perpetually concerned that others will not reciprocate their need for intimacy or provide the closeness they desire.

Those with an avoidant attachment style, on the other hand, are more uncomfortable with emotional closeness and may actively avoid it. They value their independence and may become uneasy or feel suffocated when they perceive their partner getting too close.

Fear of Abandonment or Rejection

Anxious individuals have a deep fear of abandonment and rejection. When they perceive a threat to the relationship, they may become anxious, clingy, and seek reassurance from their partner to alleviate their anxiety.

They may worry that their partner will leave them or not love them as much as they desire.

Avoidant individuals tend to have a fear of dependence and will distance themselves from their partner as a way to cope with perceived threats to their independence.

They believe that others will eventually abandon and reject them, so they may react by withdrawing emotionally or physically when they feel too close to someone.

Emotional Expressiveness

People with anxious attachment styles tend to express their emotions more intensely. They may openly share their feelings, often seeking validation and reassurance from their partner.

They can also be more vocal about relationship issues.

Avoidant individuals are typically less expressive when it comes to their emotions and needs. They may downplay their feelings and have difficulty discussing relationship problems or vulnerabilities.

As such, commitment issues tend to be prevalent in avoidant attachment as these individuals can become uncomfortable when others get too close.

Approach to Commitment

Anxious individuals often crave commitment and may be eager to move quickly into a long-term relationship. They may worry about their partner’s commitment and feel uncertain if their partner is not as enthusiastic about the relationship.

Avoidant individuals tend to struggle with commitment. They may be hesitant to enter into or maintain long-term, committed relationships because they fear losing their independence.

Trust Issues

Trust issues can be common in insecure attachment styles.

Due to their fear of abandonment, anxious attached individuals may have difficulty trusting that their partner truly cares for them and will remain committed.

They are hyper-vigilant to signs of abandonment and can become suspicious of their partner if they notice any perceived distance.

Avoidant individuals believe that others will inevitably reject them. They do not trust that others can be responsive to their needs, so instead, they rely on their own ability to take care of themselves and be self-sufficient.

Communication Style

Anxious individuals tend to express their emotions openly and intensely. They enjoy deep conversations where they can form an intimate bond and get to know someone on an emotional level.

In contrast, avoidant individuals typically have strong boundaries to keep others at an emotional distance. They prefer casual, lighthearted conversations rather than deep, emotional ones.

Generally, they do not disclose much information about themselves, their feelings, or their past.

Coping Mechanisms

Anxious individuals may cope with relationship stress by seeking reassurance, talking through issues, or actively pursuing their partner’s attention and affection.

Conflict can trigger hyper-activating strategies in anxious individuals. They may become clingy, demanding, and possessive to ensure their partner’s closeness and affection.

Avoidant individuals may cope by distancing themselves emotionally or physically, engaging in self-soothing activities, or diverting their focus away from the relationship when they feel overwhelmed.

They may push their partner away and refuse to communicate because they can feel distressed by strong emotional displays.

Relationship Satisfaction

People with anxious attachment styles may experience lower relationship satisfaction due to their constant worries about abandonment and their strong desire for reassurance and closeness.

Their heightened sensitivity to any perceived signs of rejection or neglect can lead to emotional turmoil and insecurity within the relationship.

People with avoidant attachment styles may also experience lower relationship satisfaction, primarily because of their discomfort with emotional closeness and reluctance to open up.

Their need for independence and fear of dependence can create emotional distance in the relationship. Additionally, their hesitancy to commit to a deeper emotional bond can make their partner feel rejected or unimportant, leading to further dissatisfaction.

Caregiving

Just as children derive a feeling of security from their parents during times of trouble, adults look towards spouses, family members, and friends when facing distress.

During adulthood, romantic partners are frequently the most important providers of social support and are also typically the primary attachment figure in close, adult relationships.

Anxious individuals tend to be highly attuned to the emotional needs of their partners or children. As such, they may be vigilant about their loved ones’ well-being and seek to provide constant support and validation.

They can be quick to respond to perceived distress in their loved ones and may prioritize their needs over their own.

However, this can result in hyperactive caregiving. This refers to a self-focused need for excessive emotional involvement in another’s problems. I️t can result in an intrusive, controlling, or poorly timed support provision, often incongruent with the care seeker’s needs (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007).

Anxiously attached individuals may provide help regardless of whether their partner needs assistance and affording support even in lower stress situations.

Avoidant individuals often struggle with emotional intimacy and may appear emotionally distant in their caregiving roles.

They tend to exhibit discomfort and disinterest in helping, and have difficulty understanding their partner’s feelings (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2002). They might prioritize their own independence and self-sufficiency over providing emotional support to others.

They may be less likely to offer comfort or emotional support when their partners or children are in distress, which can leave their loved ones feeling neglected or unsupported.

Additionally, avoidant caregivers can find it challenging to express love and affection openly. They might struggle to communicate their caregiving intentions or provide physical affection.

Summary

| Anxious Attachment Style | Avoidant Attachment Style | |

|---|---|---|

| Self-perception | Often perceive themselves as unworthy of love and are preoccupied with a fear of abandonment | Often perceive themselves as self-sufficient and prioritize independence over emotional intimacy. |

| View of Others | Usually perceive others as unreliable and unable to meet their needs. | Generally view others as intrusive, overly demanding, or untrustworthy. |

| Emotional Expressiveness | Tend to be highly emotional and quick to express their feelings, even to the point of seeming clingy. | Tend to suppress their emotions, and may seem detached or unresponsive in emotionally charged situations. |

| Intimacy | Seek high levels of intimacy and approval from partners, often appearing overly dependent. | Tend to be uncomfortable with closeness and emotional intimacy, prefering independence. |

| Response to Conflict | Fear rejection and abandonment during conflicts; may become overly accommodating, appeasing, or aggressive as a result. | Avoid any conflicts or discussions about feelings; might withdraw, deflect, or minimize their problems. |

Do People With Anxious and Avoidant Attachment Styles Attract Each Other?

It’s not uncommon for individuals with anxious and avoidant attachment styles to be attracted to each other and form relationships. However, research on attachment style and partner preference is still inconclusive.

Some research (e.g., Baldwin et al., 1996) supports the “similarity hypothesis,” which suggests that people prefer partners with a similar attachment style to their own.

Other research (e.g., Collins et al., 2002) supports the “complementary hypothesis,” which suggests that people choose partners who confirm their attachment-related expectations.

For example, anxious individuals prefer avoidant partners because they confirm their expectation that others are distant and cannot meet their emotional needs.

Yet another hypothesis known as the “attachment-security hypothesis” (Latty-Mann and Davis, 1996) suggests that everyone, regardless of attachment style, prefers partners with a secure attachment style.

A review on this topic found that people will make decisions based on the similarity and attachment-security hypothesis when choosing partners. That is, they prefer partners who have a similar or secure attachment style.

However, they also found that when it comes to maintaining a relationship long-term, people prefer partners that confirm their attachment-based expectations (the complementary hypothesis).

Why Is This the Case?

The researchers suggest that during the initial attraction period, people place more importance on the desired availability and responsiveness of a potential partner.

For example, an avoidant individual may prefer a person who is similarly avoidant or has a more secure attachment style.

As the relationship progresses, though, it becomes more important how their partner makes them think and feel about themselves.

This may be explained by people preferring what is familiar and “safe.” In other words, when people confirm what we think of ourselves and other people (even when this is negative), it feels accurate and reliable.

While attraction between attachment styles can lead to relationships, it’s important to note that they often come with unique challenges. The differences in attachment styles can lead to miscommunication, misunderstandings, and emotional ups and downs in the relationship.

However, with self-awareness, communication, and willingness to work on their attachment dynamics, couples with different attachment styles can build healthier, more secure relationships.

Julia Simkus edited this article.

Sources

Holmes, B.M. & Johnson, K.R. (2009). Adult attachment and romantic partner preference: a review. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26 (6-7), 833-852.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2005). Attachment theory and emotions in close relationships: Exploring the attachment‐related dynamics of emotional reactions to relational events. Personal Relationships, 12(2), 149-168.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. New York: Guilford Press.

Simpson, J.A., Steven, R.W. (2017) Adult Attachment, Stress, and Romantic Relationships. Current Opinions in Psychology. 13: 19-24.

Vollmann, M., Sprang, S., & van den Brink, F. (2019). Adult attachment and relationship satisfaction: The mediating role of gratitude toward the partner. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(11–12), 3875–3886.