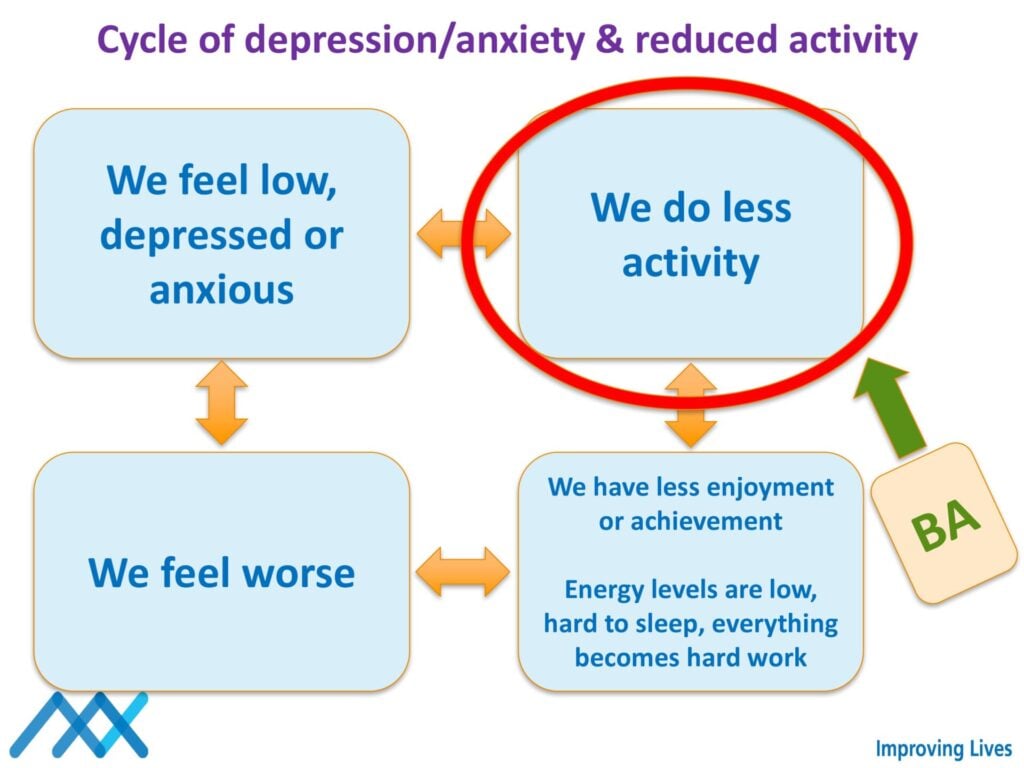

Behavioral activation (BA) is a cognitive-behavioral therapy method for depression. It illuminates the link between behavior, emotion, and thought. By modifying depressive behaviors and increasing involvement in positive activities, BA enhances mood. The central idea is that changing behavior can alter emotions and thoughts. The emphasis is on what sustains depression rather than its initial triggers.

Kitchen, C. E. W., Lewis, S., Ekers, D., Gega, L., & Tiffin, P. A. (2023). Barriers and enablers for young people, parents and therapists undertaking behavioural activation for depression: A qualitative evaluation within a randomised controlled trial. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 96(2), 504-524. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12452

Key Points

- This qualitative study explored experiences of behavioral activation (BA) for youth depression across 6 adolescents, 5 parents, and 5 therapists in UK mental health services.

- Motivation, tailored parental involvement, and positive therapist relationships facilitated BA treatment, while mismatches with learning style, unaddressed comorbidities, lack of parental support, and therapist doubts hindered progress.

- Flexibility is needed when implementing manualized BA to meet varying individual needs while retaining core components.

- Benchmarking best practice BA and customizing delivery could optimize adherence and outcomes in real-world settings.

- Further research on BA modifications for specific populations and therapist training is warranted.

Rationale

Depression affects 8-34% of adolescents globally, causing severe current and future impairment (Shorey et al., 2022).

Despite the need, many youths lack access to evidence-based therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) due to limited specialized staff (Kitchen et al., 2021).

Brief, manualized approaches deliverable by diverse professionals, like behavioral activation (BA), could improve access to effective adolescent depression treatment (Ekers et al., 2011; Malik et al., 2021).

While quantitative trials have shown promise, few studies qualitatively explored youths’, parents’, and therapists’ experiences during BA.

This qualitative study by Kitchen et al. (2023) explored adolescents, parents, and therapists’ real-world perspectives to refine BA implementation in UK child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS).

Their rationale aligns with Medical Research Council guidance to optimize complex interventions through qualitative participant feedback (Skivington et al., 2021).

Method

This qualitative study was nested within a BA feasibility randomized controlled trial with depressed adolescents ages 12-17 in UK mental health services.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 6 adolescents, 5 parents, and 5 therapists who delivered BA.

The therapists had varying roles and experience levels. Inductive thematic analysis was utilized to elucidate key factors influencing BA delivery and engagement.

Sample:

- 6 adolescents ages 13-17 with mild to severe depression at baseline, 3 no longer depressed after treatment

- 5 parents, mostly mothers

- 5 therapists delivering BA with different backgrounds and NHS bands

- Most adolescents had 8 BA sessions, ranging 2-8 sessions over 4-13 weeks

Qualitative Analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted per Braun and Clarke’s (2006) principles.

Transcripts were coded to develop an initial framework, refined through consensus with experienced researchers, and final themes identified. Contextual clinical information aided analysis.

Results

Four key themes were identified: intervention delivery, adolescent needs, parent involvement, and therapist factors.

1. Intervention Delivery:

- Weekly BA sessions optimally balanced completing tasks and retaining learning versus longer gaps being counterproductive.

- Average 49 minute sessions worked well, with 30 minutes feeling too short.

- While 8 sessions seemed adequate, flexibility could allow more sessions to address comorbidities or fewer due to limited therapist availability.

- Follow-up sessions could prevent “cliff-edge” anxiety ending regular contact.

- Manual materials need refining for brevity and use of graphics/technology over paper-heavy content.

2. Adolescent Needs:

- Motivation facilitated progress, while low motivation and commitment hindered success.

- Unaddressed comorbid conditions like anxiety, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and learning differences were barriers.

- Cognitive or memory difficulties impeded remembering content between sessions.

3. Parent Involvement:

- Tailoring parental involvement to the adolescent’s needs and preferences was optimal, with flexibility for each family.

- Parent attendance could reinforce learning and provide support, but risked inhibiting adolescent sharing.

4. Therapist Factors:

- Positive client-therapist relationships were important to adolescents.

- Lack of confidence in BA as suitable standalone treatment or for complex cases was a hindrance.

- Prior training and comfort with structured approaches influenced therapist delivery.

Implications

- Demonstrates the vital need for flexibility when implementing manualized BA in clinical practice to address varying individual needs

- Tailoring parental involvement, addressing adolescent motivation, and customizing BA format could significantly improve experiences and outcomes

- Highlights importance of therapist training and addressing preconceptions about BA applicability to facilitate dissemination

- Provides direction for research on BA modifications for conditions like ASD and optimal flexibility

- Elucidates key considerations for implementing BA specifically within child and adolescent mental health services

Strengths & Limitations

The study had many methodological strengths, including:

- Comprehensively captured perspectives from all key participant groups involved in BA delivery – adolescents, parents, and therapists.

- Aligned with established guidance on optimizing complex interventions through participant feedback.

- Interviews were conducted by a university researcher not involved in patient care to facilitate openness.

- Focused on eliciting both positive and negative experiences to enable a balanced perspective

- Captured experiences across various stages of BA treatment completion and durations.

However, this thematic analysis was limited in a few ways:

- The small sample was restricted to one UK region.

- Therapist characteristics and fidelity were not systematically examined.

- Co-interviewing parents and youth may have influenced responses.

- Experiences of youth who dropped out were not captured.

Conclusion

The study provided crucial insights into real-world perspectives on implementing manualized BA for youth depression.

Key facilitators were adolescent motivation, tailored parental roles, and positive therapist alliances. Barriers included developmental and comorbidity considerations, parental difficulties, and therapist doubts in BA applicability.

Allowing flexibility within a standardized BA framework could optimize delivery and outcomes by customizing it to varying needs while retaining core components.

Further research should:

- Examine the experiences of adolescents who discontinue BA to identify barriers

- Develop recommendations for optimally involving parents while avoiding adverse effects

- Clarify optimal flexibility, modifications for subgroups like ASD, and therapist training to facilitate dissemination.

References

Primary Paper

Kitchen, C. E. W., Lewis, S., Ekers, D., Gega, L., & Tiffin, P. A. (2023). Barriers and enablers for young people, parents and therapists undertaking behavioural activation for depression: A qualitative evaluation within a randomised controlled trial. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 96(2), 504-524. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12452

Other References

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Ekers, D., Godfrey, C., Gilbody, S., Parrott, S., Richards, D. A., Hammond, D., & Hayes, A. (2011). Cost utility of behavioural activation delivered by the non-specialist. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 510-511. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.090266

Kitchen, C. E. W., Lewis, S., Ekers, D., Gega, L., & Tiffin, P. A. (2023). Barriers and enablers for young people, parents and therapists undertaking behavioural activation for depression: A qualitative evaluation within a randomised controlled trial. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 96(2), 504-524. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12452

Malik, K., Ibrahim, M., Bernstein, A., Kodihalli Venkatesh, R., Rai, T., Chorpita, B., & Patel, V. (2021). Behavioral activation as an ‘active ingredient’ of interventions addressing depression and anxiety among young people: A systematic review and evidence synthesis. BMC Psychology, 9, Article 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00661-7

Martin, F., & Oliver, T. (2019). Behavioral activation for children and adolescents: A systematic review of progress and promise. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(4), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1207-3

Shorey, S., Ng, E. D., & Wong, C. H. J. (2022). Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(2), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12358

Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S. A., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J. M., Boyd, K. A., Craig, N., French, D. P., McIntosh, E., Petticrew, M., Rycroft-Malone, J., White, M., & Moore, L. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 374, n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061

Tindall, L., Toner, P., Mikocka-Walus, A., & Wright, B. (2021). Perceptions of and opinions on a computerized behavioral activation program for the treatment of depression in young people: Thematic analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(4), Article e19743. https://doi.org/10.2196/19743

Further Reading

Behavioral activation for depression (worksheet)

Learning Check

- What strategies can help motivate adolescents to engage more fully in BA treatment?

- How might BA be adapted to better suit young people with learning differences, ASD, or other comorbidities?

- What are effective ways to involve parents that provide benefits without hindering adolescent sharing?

- How can therapists be better prepared and supported to deliver BA as intended to diverse youths?

- What system-level implementation supports (training, supervision, etc.) facilitate BA adoption in youth mental health settings?

- How can we promote therapist openness to evidence-based yet brief therapies like BA as valuable options for youths?