On This Page:

In psychology, attachment theory describes the emotional bonds people form with caregivers and how these attachment styles can influence their relationships throughout life.

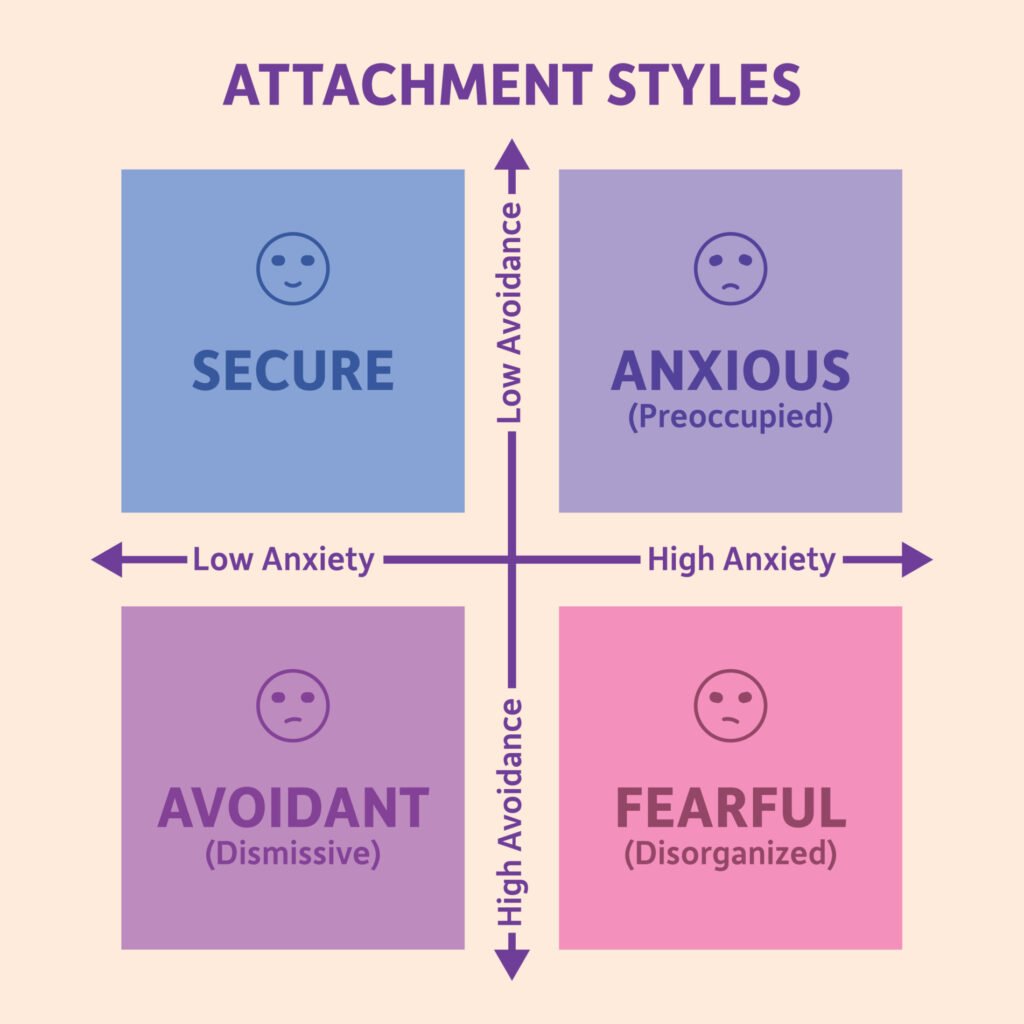

There are two main attachment styles relevant to adult romantic relationships: insecure attachment and secure attachment.

Secure attachment in adults is typically characterized by trust, stability, and a balance between intimacy and independence. Insecure attachment (anxious, avoidant, or disorganized) tends to involve emotional distance, inconsistent reactions to intimacy and conflict, and a fear of abandonment.

Secure attachment is associated with low anxiety and low avoidance. Anxious attachment is associated with high anxiety and low avoidance. Dismissive attachment is associated with low anxiety and high avoidance. And disorgnaized attachment is associated with high anxiety and high avoidance.

From the moment we are born, humans are innately programmed to build connections. Depending on the quality of our care and environment growing up, we build internal models of ourselves, others, and relationships that form our attachment style.

This innate drive to bond and seek proximity with our caregivers is a mechanism that allows us to survive the perils of infancy and childhood. As we grow up, building relationships and bonding with other people continues to be vital for our well-being and survival.

Although caregivers have an important role to play, our relationships in adolescence and young adulthood can also impact our attachment style.

Secure Attachment

When caregivers attend to their child’s needs and bids for affection consistently, the child will likely develop a secure attachment style.

Securely attached individuals have a positive view of themselves and others. They are comfortable with intimacy and independence and are able to build stable and healthy relationships. They also tend to have a positive view of their childhood and upbringing.

An individual with a secure attachment style exhibits a consistent, interdependent, and confident relationship-related style. They typically feel worthy of love and feel confident that their emotional needs will be met.

They can form deep, satisfying, and lasting bonds with their partners and are comfortable with the consistent presence of intimacy and support.

Securely attached adults strike a healthy balance between being emotionally close and maintaining their individuality. They can engage in intimate relationships while also valuing their autonomy.

Insecure Attachment

Insecure attachment typically develops in children who grew up with caregivers who were not responsive to their emotional needs. Insecure attachment is divided into three subtypes: avoidant (or dismissive-avoidant), anxious (or preoccupied), and disorganized (or fearful-avoidant).

While there are distinctions between the three types of insecure attachment styles, insecurely attached individuals all tend to struggle with trust, intimacy, and communication.

Anxious Attachment

Anxiously attached individuals are often preoccupied with their relationships. They have a strong fear of abandonment and seek constant reassurance from their partners. Because of this, they also may appear clingy and overly dependent.

Those with an anxious attachment style tend to have a strong desire for emotional closeness, and may become overly dependent on their partner for self-esteem boosts and validation. Autonomy and independence can make them feel anxious, and they tend to be sensitive to any signs of distance or rejection.

In addition, they may struggle with effective communication and boundaries due to their intense need for closeness.

Avoidant Attachment

Avoidant attachment style is a psychological and emotional pattern characterized by an individual’s tendency to avoid emotional closeness and dismiss the importance of intimate relationships, often as a self-protective measure.

Those with an avoidant attachment style value independence and self-sufficiency and tend to suppress their emotional needs and avoid intimacy. They often maintain emotional distance in relationships and struggle to express or acknowledge their needs.

This attachment style usually develops as a result of emotional rejection and neglect from primary caregivers in early childhood.

Disorganized Attachment

The disorganized attachment subtype often results from unresolved past traumas or inconsistent caregiving during childhood.

Individuals with this attachment style may exhibit erratic and inconsistent behavior in relationships, with a mix of anxious and avoidant tendencies. They sometimes seek closeness and at other times push their partners away.

People with this attachment style experience a combination of intense anxiety about their relationships and discomfort with emotional closeness. This can lead to conflicting behaviors in relationships, with a push-pull dynamic.

What Are the Differences Between Insecure and Secure Attachment?

The differences between insecure and secure attachment can greatly impact the dynamics and quality of our relationships.

While this article discusses the general patterns and behaviors of different attachment styles, it’s important to remember that attachment styles are not fixed or categorical.

| Secure | Insecure Anxious | Insecure Avoidant | Insecure Disorganized | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-perception | Positive, confident, and deserving of love | Often self-doubting | Self-sufficient and independent | Chaotic, fluctuating between feelings of worthiness and unworthiness |

| View of Others | Generally reliable and helpful | Unreliable and unable to meet their needs | Intrusive, overly demanding, or untrustworthy | Mixed feelings and ambivalence |

| Emotional Expressiveness | Open and comfortable with expressing emotions | Highly emotional and quick to express their feelings, often seeming clingy | Detached or unresponsive in emotionally charged situations | Struggle with managing and expressing emotions; may switch between extreme emotional states |

| Intimacy | Comfortable with closeness and emotional intimacy, but also able to maintain a sense of independence | Seek high levels of intimacy and approval from partners, often appearing overly dependent | Tend to be uncomfortable with closeness and emotional intimacy, preferring independence | Have difficulty forming stable, intimate relationships due to conflicting desires for closeness and distance |

| Response to Conflict | Constructive and adaptive | Emotional and anxious | Defensive and withdrawn | Erratic and intense |

| Relationships | Generally balanced, characterized by trust, stability, and satisfaction | Tumultuous, due to their clinginess and intense emotional attachment | Lack deep intimacy and emotional closeness | Turbulent and unpredictable |

| Perception of Partner’s Availability | Realistic | Often feel that their partner is less available and less caring than they actually are | Tend to overestimate or distrust their partner’s availability | Often confused or uncertain about their partner’s availability |

| Coping Strategies | Adaptive, balancing their needs and their partner’s needs | “Protest behavior” including excessive contact or attempts to incite jealousy | Deactivation strategies, such as focusing on their independence and suppressing their feelings | Erratic and unpredictable |

Below, we discuss how insecure attachment differs from secure attachment in more detail.

Emotional Availability

Emotional availability refers to an individual’s ability and willingness to be open, responsive, and emotionally present in a relationship.

Securely attached individuals tend to be emotionally available to their partners. They are open and responsive to their partner’s emotional needs and feel comfortable expressing their own feelings. They can provide emotional support and closeness when needed but also respect their partner’s boundaries and independence.

Avoidantly attached individuals are typically less emotionally available. They may downplay or dismiss their own emotions and avoid discussing their feelings, making it challenging for them to be intimate or emotionally available partners.

Anxious individuals may struggle with emotional availability in different ways. Although they can be described as emotionally available, their experiences and expressions of emotions are often underpinned by anxiety. They might overwhelm their partners with their emotional demands, seeking reassurance and closeness excessively.

Those with a disorganized attachment style exhibit erratic emotional availability, vacillating between intense emotional closeness and emotional distancing. This inconsistency can create confusion and instability in their relationships.

Communication

Insecure attachment styles differ from secure attachment in several ways when it comes to communication within relationships.

Securely attached individuals generally have open and effective communication styles. They are comfortable expressing their thoughts, feelings, and needs in a clear and straightforward manner. They are also good listeners, showing empathy and understanding when their partners communicate.

People with insecure attachment styles tend to struggle with clear and effective communication.

Avoidantly attached individuals are less expressive when it comes to their emotions and needs. They have difficulty opening up and sharing their feelings, often downplaying the importance of emotional discussions. This can result in difficulty resolving conflicts through communication.

Anxious individuals often communicate from a place of anxiety. They often fear rejection or abandonment, leading to a tendency to overanalyze and overcommunicate their emotions and concerns. This can create communication challenges, as their heightened anxiety may cloud their ability to express themselves calmly and assertively.

People with a disorganized attachment style may exhibit inconsistent communication patterns. They struggle to express themselves clearly and coherently, and their emotional responses can be erratic. This inconsistency in communication can lead to confusion and misunderstandings in their relationships.

Trust and Intimacy

Securely attached individuals generally have a healthy level of trust both in themselves and in their partners. They tend to feel emotionally secure in their relationships, confident that their needs will be met and that their partners will be there for them in difficult times.

They also are comfortable with emotional intimacy and can establish deep, meaningful connections with their partners.

Anxious individuals often struggle with trust and intimacy in relationships. They have heightened fears of abandonment and rejection, leading to a constant need for reassurance from their partners.

They often crave emotional intimacy but struggle with excessive neediness and insecurity.

Avoidantly attached individuals have difficulty trusting others with their emotions and vulnerability. They tend to downplay the importance of emotional intimacy and may be skeptical about relying on their partners for emotional support.

In terms of intimacy, they tend to distance themselves and resist emotional closeness.

Those with disorganized attachment have mixed feelings about trust and intimacy. They vacillate between wanting closeness and fearing it, leading to a conflicted and unpredictable approach to trust and intimacy in relationships.

Relationship Satisfaction

Secure attachment tends to be associated with relationship satisfaction. Securely attached individuals feel confident in themselves and their partners, which contributes to a sense of security and contentment in the relationship.

They are typically skilled at constructive conflicts resolution and are more likely to provide and receive emotional support in a balanced and reciprocal manner.

Anxious individuals often experience more turbulent and emotionally charged relationships as their constant need for reassurance and fear of abandonment can create stress and strain in the relationship.

They are more prone to jealousy and insecurity, which can lead to conflicts and relationship dissatisfaction.

Avoidantly attached individuals tend to create emotional distance in their relationships, which can lead to a lack of emotional intimacy. This emotional distance can leave their partners feeling unfulfilled and disconnected.

Those with disorganized attachment often have turbulent and unpredictable relationships. The inconsistent trust and intimacy patterns make it challenging to establish a stable, satisfying relationship.

Relationship Stability

Securely attached individuals tend to have long-lasting and stable relationships. They have a strong sense of trust in themselves and their partners, which contributes to relationship stability.

Secure individuals are generally better at resolving conflicts, providing and receiving emotional support, and creating a foundation of trust and emotional security in their relationships.

Anxious individuals often experience more turbulent relationships. Their constant need for reassurance, fear of abandonment, and jealousy can lead to emotional ups and downs, which may result in relationship instability.

Avoidantly attached individuals tend to create emotional distance in their relationships. Their reluctance to engage in emotional intimacy creates a lack of connection, which can affect relationship stability over time.

Those with disorganized attachment often have unpredictable relationships. Their mixed feelings, erratic behavior, and conflicted needs for closeness and distance can lead to frequent conflicts and instability.

Emotion Regulation

Attachment styles, whether secure or insecure, play a significant role in how individuals regulate their emotions within relationships.

Securely attached individuals tend to have a more balanced and adaptive approach to emotion regulation. They have developed effective coping strategies for dealing with both positive and negative emotions, enabling them to navigate the ups and downs of a relationship without experiencing extreme emotional distress.

Anxious individuals often struggle with intense emotional turmoil and reactivity. They may experience heightened anxiety, fear, and insecurity in response to perceived threats to the relationship.

On the other hand, avoidantly attached individuals tend to suppress their emotions, especially vulnerable ones. They may downplay or dismiss their feelings to maintain emotional distance and often have difficulty seeking emotional support from their partners.

Those with disorganized attachment exhibit erratic and unpredictable patterns of emotional regulation. Their mixed feelings about closeness and distance can lead to conflicting emotional responses, making it challenging to regulate emotions in a coherent manner.

Self-Worth

Securely attached individuals tend to have a positive and healthy self-view. They see themselves as worthy of love, respect, and care, both from themselves and from others.

Anxious individuals often seek external validation to bolster their self-worth. Their self-esteem may fluctuate depending on the status of their relationships (i.e., when the relationship is going well, they may feel more positive about themselves, but setbacks can lead to self-doubt).

They also rely heavily on their partners’ reassurance and attention to feel good about themselves.

Avoidantly attached individuals often place a strong emphasis on self-sufficiency and independence. They have difficulty accepting love and care from others, which can impact their sense of self-worth in relationships.

Disorganized individuals have a mixed self-view. They may struggle with inconsistent feelings about their self-worth, vacillating between self-doubt and self-assurance.

This attachment style often stems from past traumatic experiences, which can have a profound impact on an individual’s self-perception.

Coping Mechanisms

Attachment styles, whether secure or insecure, influence the coping mechanisms individuals use to manage stress, uncertainty, and challenges in relationships.

Securely attached individuals tend to employ adaptive and effective coping strategies when faced with relationship difficulties or life stressors. They are more likely to seek support from their partners and friends when needed; use problem-solving approaches to address conflicts and challenges; and express their feelings and concerns openly and constructively.

Although they might be maladaptive in the long term, insecure attachment styles are in essence coping mechanisms. Their strategies (e.g., seeking reassurance, emotional suppression, withdrawal) allowed them to cope with their environment when they were growing up.

However, these can create challenges in relationships and affect their ability to manage stress and uncertainty effectively.

Avoidantly attached individuals often suppress their emotions, especially vulnerable ones. They may avoid discussing their feelings or seeking emotional support from their partners.

They may withdraw or emotionally distance themselves when faced with stress or conflict and tend to rely on self-sufficiency and self-reliance.

Anxious individuals may rely on seeking constant reassurance from their partners to alleviate their fears and anxieties. They tend to overly depend on their partners to soothe their emotional turmoil, potentially creating strain in the relationship.

Disorganized individuals have a wide array of coping strategies depending on the situation and their internal conflicts. They struggle with conflicting responses, vacillating between seeking closeness and distancing themselves as coping mechanisms.

Can an Insecure Attachment Become Secure?

Although attachment styles are relatively stable over time, they are not fixed or permanent.

They can evolve and change over time, and someone with an insecure attachment can become more secure with self-awareness, personal growth, and therapeutic interventions

One study on “Earning Secure Attachment” demonstrated that the process of transforming one’s attachment style is possible but requires intentional effort on multiple levels.

Recognizing and understanding one’s own attachment style is the first step toward change. Self-awareness allows individuals to identify how their attachment style may be impacting their relationships and emotional well-being.

Being in a relationship with a securely attached partner can also be particularly beneficial in fostering a more secure attachment style. Engaging in healthy, supportive relationships provides an opportunity to experience secure attachment patterns firsthand.

Changing the relationship you have with yourself is important too. This can involve setting healthy boundaries, engaging in regular self-care, and recognizing one’s intrinsic worth.

It also means learning to be comfortable with closeness and letting go of fears – the fear of abandonment, fear of rejection, and fear of intimacy and commitment.

For some individuals, past traumatic experiences may have contributed to their insecure attachment style. Addressing and healing from these traumas can be a key step toward developing a more secure attachment.

Working with a therapist or counselor, especially one trained in attachment theory and techniques, can be highly beneficial. Therapy can help individuals explore the root causes of their attachment style, develop insight into their behavior and emotional patterns, and learn healthier ways to relate to others.

Your attachment style and individual experience will determine the best approach for your journey of change and healing.

It’s important to acknowledge, though, that changing attachment styles is a gradual process that requires practice and patience. You must be forgiving of yourself and recognize that setbacks may occur.

Personal Accounts

Here are some personal accounts of people earning a secure attachment style taken from Olufowote et al. (2019):

Building Self-Worth

“Once I discovered I have value apart from everyone else. . . It’s like I’ve decided my time and energy is valuable so I’m gonna spend it on people who also value me.”

“It’s a lot of falling and then realizing, ‘Oh, this place isn’t good.’ And then figuring out, ‘Okay, where did I go [wrong]?’”

“Just me, just who I am, that’s good enough.”

“It’s easier to be okay with you when you’re not trying to be who you think they want you to be.”

“I think the more comfortable I am with myself, I will seek out relationships that are more compatible with who I am.”

Developing Self-Awareness

“Once I . . . [realized] my mother couldn’t trust others but even more so couldn’t trust her own opinion, I told myself I didn’t want that. So that awareness helped change it for me.”

“I grew up with blamers. . . it was always someone else’s fault, [and] I started to recognize that pattern in myself.”

Educating Yourself on Attachment Theory

“I think the more education I get, the more I’m able to apply it to my own life.”

Having a Secure Role Model

“The changing force for me was I had somebody who dug his heels in and said, ‘I’m not going anywhere, for better or worse.’”

“I knew I wanted to do it differently. So, I sought out people that looked like they were doing well.”

“Developing really good friendships that were reciprocal instead of one-sided showed me it wasn’t all people that were [unsafe]. I had the ability to look at both [positive and negative relationships] and say, ‘This one is better.'”

“If I had never seen [a secure example] and only had bad experiences, I know [change] would have been a lot harder.”

“[He said to me], ‘You don’t know what you’re doing. There’s a different way to live; let me show you how to do that.’ I grew so much in those 6 months that I was mentored by that guy. I think that was just a shift in my culture of understanding. And maybe being a man was more about being able to admit my weaknesses and ask for help rather than just trying to figure it out on my own and blindly stumble along.”

Setting Boundaries

“I’ve had to place a little bit of distance there for [my mom and me] to have any kind of a healthy relationship.”

Healing the Past/ Seeing a Therapist

“[My therapist] gave me some insight in sharing someone else’s story of pain. So, I was able to revisit my mom with a new lens. That was growth also. That was a huge step forward.”

Letting Go of Fear

“[I took a] leap of faith,” and “actively working on the willingness to trust,” and “a willingness to set aside your own ego and objectively give someone the benefit of the doubt instead of letting your anxiety take over.”

Sources

Candel, O.S. & Turliuc, M.N. (2019). Insecure attachment and relationship satisfaction: A meta-analysis of actor and partner associations. Personality and Individual Differences, 147: 190-199.

Olufowote, R.A.D., Fife, S.T., Schleiden, C. & Whiting, J.B. How Can I Become More Secure? A Grounded Theory of Earning Secure Attachment. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 46 (3): 489-506.

Schachner, D. A., Shaver, P. R., & Mikulincer, M. (2003). Adult attachment theory, psychodynamics, and couple relationships. Attachment processes in couple and family therapy, 18-42.

Sheinbaum, T., Kwapil, T.R., Ballespí, S., Mitjavila, M., Chun, C.A., Silvia, P.J. & Barrantes-Vidal N. (2015). Attachment style predicts affect, cognitive appraisals, and social functioning in daily life. Frontiers in Psychology, 18 (6), 296.

Simpson, J.A. & Rholes, W.S. (2017). Adult Attachment, Stress, and Romantic Relationships. Current Opinions in Psychology, 13, 19-24.

Julia Simkus edited this article.