The medical model of mental illness treats mental disorders in the same way as a broken arm, i.e., there is thought to be a physical cause.

This model has been adopted by psychiatrists rather than psychologists.

Supporters of the medical model consequently consider symptoms to be outward signs of the inner physical disorder and believe that if symptoms are grouped together and classified into a ‘syndrome,’ the true cause can eventually be discovered and appropriate physical treatment administered.

Assumptions

The biological approach to psychopathology believes that disorders have an organic or

physical cause. The focus of this approach is on genetics, neurotransmitters, neurophysiology, neuroanatomy, etc.

The approach argues that mental disorders are related to the physical structure and functioning of the brain.

Behaviors such as hallucinations are “symptoms” of mental illness, as are suicidal ideas or extreme fears such as phobias about snakes and so on. Different illnesses can be identified as “syndromes,” clusters of symptoms that go together and are caused by the illness.

These symptoms lead the psychiatrist to make a “diagnosis,” for example, “this patient is suffering from a severe psychosis; he is suffering from the medical condition we call schizophrenia.”

What is happening here? The doctor makes a judgment of the patient’s behavior, usually in a clinical interview after a relative or general practitioner has asked for an assessment.

The doctor will judge that the “patient” is exhibiting abnormal behavior by asking questions and observing the patient.

Judgment will also be influenced heavily by what the relatives and others near the patient say and the context – is mental illness more likely to be diagnosed in a mental hospital?

Diagnostic Criteria

In psychiatry, the psychiatrist must be able to validly and reliably diagnose different mental illnesses.

The first systematic attempt to do this was by Emil Kraepelin, who published the first recognized textbook on psychiatry in 1883.

Kraepelin claimed that certain groups of symptoms occur together sufficiently frequently for them to be called a disease. He regarded each mental illness as a distinct type and set out to describe its origins, symptoms, course, and outcomes.

Kraepelin’s work is the basis of modern classification systems. The two most important are:

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)

This is the classification system used by the American Psychiatric Association. The first version (DSM 1) was published in 1952. The latest version is DSM V, published in 2013.

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD)

This is published by The World Health Organisation. Mental disorders were included for the first time in 1948 (ICD 6). The current version is ICD 10, published in 1992.

In order to diagnose someone, you would usually need some/all of the following:

- Clinical interview

- Careful observation of behavior, mood states, etc.

- Medical records

- Psychometric tests

On the basis of the diagnosis, the psychiatrist will prescribe treatment such as drugs, psychosurgery, or electroconvulsive therapy. However, since the 1970s, psychiatrists have predominantly treated mental illnesses using drugs.

Critical Evaluation

The traditional categorical diagnostic systems used in mental health, like the DSM and ICD, were developed primarily for clinical utility to categorize mental disorders.

However, researchers have identified a number of limitations of these categorical systems for research purposes (Cuthbert & Kozak, 2013; Kotov et al., 2017):

- Heterogeneity within diagnoses – People with the same diagnosis may exhibit very different symptom profiles, so two people with “major depression” could share few common symptoms (Fried & Nesse, 2015). This makes it hard to draw generalizable conclusions about the disorder.

- Comorbidity and symptom overlap – Many symptoms, like insomnia or irritability, occur across numerous diagnoses. This makes teasing apart distinct disorders difficult when they share common symptom dimensions (Haslam et al., 2020).

- Arbitrary diagnostic thresholds – There’s little evidence that mental disorders naturally fall into discrete categories versus lying along a continuum. However arbitrary thresholds are set for when a diagnosis applies (Haslam et al., 2020). This doesn’t fit a dimensional model of psychopathology.

- Low reliability and validity – Diagnoses based on categorical systems can have poor inter-rater reliability, test-retest reliability, and validity in terms of linking to biological correlates or treatment response (Regier et al., 2013).Studies have shown that diagnosis is not a reliable tool. Rosenhan (1973) conducted an experiment where the aim was to see whether psychiatrists could reliably distinguish between people who were mentally ill and those who were not.

The study consists of two conditions from which a hospital was informed that patients would be coming that are not actually mentally ill, when in fact, no patients were sent at all. In this condition, the psychiatrists only diagnosed 41 out of 193 patients as being mentally ill when in reality, all patients were mentally ill.

In the other conditions, eight people were told to report at the hospital that they heard noises in their heads. As soon as they were administered, they behaved normally. The doctors in this condition still classified these patients as insane, with a case of dormant schizophrenia.

Rosenhan concluded that no psychiatrist could easily diagnose the sane from the insane. Though Rosenhan delivered a very accurate report on patients’ diagnoses, Rosenhan was criticized for deceiving the hospital by claiming that sane patients were being sent over, though none were actually sent.

- Poor fit for tracking individual symptoms – Diagnostic categories are static and don’t capture dynamic changes in individual symptoms over time (Fisher et al., 2018).

- Questionable biological basis – The underlying biological and genetic basis for current diagnostic categories remains unclear (Cuthbert & Kozak, 2013).

This has led to calls for approaches focused more on dimensions, mechanisms, or neurobiological correlates rather than discrete categories (Insel et al., 2010).

Approaches like the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP), network models, and the NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) aim to move beyond categorical diagnoses to study more fine-grained elements of mental health and illness.

Schizophrenia

The main biological explanations of schizophrenia are as follows:

- Genetics – there is considerable evidence of a genetic predisposition to develop schizophrenia.

- Biochemistry – the dopamine hypothesis argues that elevated levels of dopamine are related to symptoms of schizophrenia.

- Neuroanatomy – differences in brain structure (abnormalities in the frontal and

the pre-frontal cortex and enlarged ventricles) have been identified in people with schizophrenia.

Depression

The main biological explanations of depression are as follows:

- Genetic – there is considerable evidence that the predisposition to develop

depression is inherited. - Biochemistry, e.g., Amine hypothesis – low levels of monoamines, predominantly noradrenaline and serotonin.

- Neuroanatomy – damage to amine pathways in post-stroke patients.

- Neuroendocrine (hormonal) factors – the importance of stress hormones (e.g., cortisol) and overactivity of the HPA axis, which is responsible for the stress response.

OCD

The main biological explanations of OCD are as follows:

- Genetic – there is some evidence of a tendency to inherit OCD, with a gene

(Sapap3) recently identified. - Biochemistry – serotonin deficiency has been implicated.

- Neuroanatomy – dysfunctions of the orbital frontal cortex ( OFC ) over-activity in

basal ganglia and caudate-nucleus thalamus have been proposed. - Evolutionary – adaptive advantages of hoarding, grooming, etc.

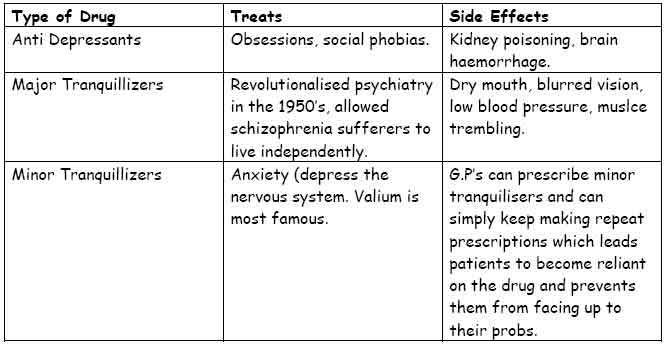

Drug Treatment

The film one flew over the cuckoo’s nest demonstrates the way in which drugs are handed out like smarties merely to keep the patients subdued.

Note also in the film that the same type of drug is given to every patient with no regard for the individual’s case history or symptoms; the aim is merely to drug them up to the eyeballs to shut them up!

The main drugs used in the treatment of depression, anxiety, and OCD are monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), tricyclic antidepressants, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Antipsychotic drugs can be used to treat schizophrenia by blocking d2 (dopamine) receptors. There are different generations of

antipsychotics:

- Typical antipsychotics – e.g., chlorpromazine, block d2 receptors in several brain

areas. - Less typical antipsychotics – e.g., pimozide, often used as a last resort when other

drugs have failed. - Atypical antipsychotics – e.g., risperidone. Some atypicals also block serotonin

receptors.

Effectiveness

- Anti-psychotics have long been established as a relatively cheap, effective treatment,

which rapidly reduce symptoms and enable many people to live relatively normal

lives (Van Putten, 1981). - Relapse is likely when drugs are discontinued.

- Drug treatment is usually superiour to no treatment.

- Between 50 – 65% of patients benefit from drug treatments.

Appropriateness

- Drugs do not deal with the cause of the problem. They only reduce the symptoms.

- Anti-psychotics produce a range of side effects, including motor tremors and weight gain. These lead a proportion of patients to discontinue treatment.

- Patients often welcome drug therapy, as it is quicker, easier, and less threatening than talk therapy.

- Some drugs cause dependency.

- Ethical issues, including informed consent and the dehumanizing effects of some

treatments.

Electro Convulsive Therapy (ECT)

Electro Convulsive Therapy (ECT) began in the 1930s after it was noticed that when cows are executed by electric shocks, they appear to convulse as if they have an epileptic shock.

The idea was extrapolated to humans as a treatment for schizophrenia on the theoretical basis that nobody can have schizophrenia and epilepsy together, so if epilepsy is induced by electric shock, the schizophrenic symptoms will be forced into submission!

ECT was used historically but was largely abandoned as a treatment for schizophrenia after the discovery of antipsychotic drugs in the 1950s but it has recently been re-introduced in the USA.

In the UK, the use of ECT is not recommended by NICE except in very particular cases (mainly for catatonic schizophrenia). However, it is sometimes used as a last resort for treating severe depression.

ECT can be either unilateral (electrode on one temple) or bilateral (electrodes on both

temples).

The procedure for administering ECT involves the patient receiving a short-acting anesthetic and muscle relaxant before the shock is administered. Oxygen is also administered.

A small amount of current (about 0.6 amps) passed through the brain lasting for about half a second. The resulting seizure lasts for about a minute. ECT is usually given three times a week for up to 5 weeks.

ECT should only be used when all else fails! Many argue that this is sufficient justification for its use, especially if it prevents suicide. ECT is generally used in severely depressed patients for whom psychotherapy and medication have proven to be ineffective.

It can also be used for those who suffer from schizophrenia and manic depression. However, Sackheim et al. (1993) found that there was a high relapse rate within a year suggesting that relief was temporary and not a cure.

There are many critics of this extreme form of treatment, especially of its uncontrolled and unwarranted use in many large, understaffed mental institutions where it may be used simply to make patients docile and manageable or as a punishment (Breggin 1979).

ECT side effects include impaired language and memory as well as loss of self-esteem due to not being able to remember important personal facts or perform routine tasks.

ECT is a controversial treatment, not least because the people who use it are still unsure of how it works – a comparison has been drawn with kicking the side of the television set to make it work.

There is a debate on the ethics of using ECT, primarily because it often takes place without the consent of the individual, and we don’t know how it works!

There are three theories as to how ECT may work:

- The shock literally shocks the person out of their illness, as it is regarded as a punishment for inappropriate behavior.

- Biochemical changes take place in the brain following the shocks which stimulate particular neurotransmitters.

- The associated memory loss following shock allows the person to start afresh. They literally forget they were depressed or suffering from schizophrenia.

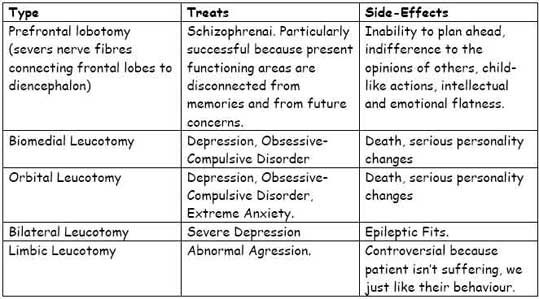

Psychosurgery

As a last result, when drugs and ECT have apparently failed, psychosurgery is an option. This basically involves either cutting out brain nerve fibers or burning parts of the nerves that are thought to be involved in the disorder (when the patient is conscious).

The most common form of psychosurgery is a prefrontal lobotomy.

Unfortunately, these operations have a nasty tendency to leave the patient vegetablized or ‘numb’ with a flat personality, shuffling movements, etc., due to their inaccuracy. Moniz ‘discovered’ lobotomy in 1935 after successfully snatching out bits of chimps’ brains.

It didn’t take long for him to get the message that his revolutionary treatment was not so perfect; in 1944, a rather dissatisfied patient called his name in the street and shot him in the spine, paralyzing him for life! As a consolation, he received the Nobel prize for his contribution to science in 1949.

Surgery is used only as a last resort when the patient has failed to respond to other forms of treatment and their disorder is very severe. This is because all surgery is risky, and the effects of neurosurgery can be unpredictable. Also, there may be no benefit to the patient, and the effects are irreversible.

Psychosurgery has scarcely been used as a treatment for schizophrenia since the early 1970s, when it was replaced by drug treatment.

There are four major types of lobotomy :

BBC Radio 4: The Lobotomists. This program tells the story of three key figures in the strange history of lobotomy – and for the first time, explores the popularity of lobotomy in the UK in detail.

Evaluation of The Medical Model

Strengths

- It is viewed as objective, being based on mature biological science.

- It has given insight into the causes of some conditions, such as GPI and Alzheimer’s disease, an organic condition causing confusion in the elderly.

- Treatment is quick and, relative to alternatives, cheap and easy to administer. It has proved to be effective in controlling serious mental illnesses like schizophrenia, allowing patients who would otherwise have to remain in the hospital to live at home.

- The sickness label has reduced the fear of those with mental disorders. Historically, they were thought to be possessed by evil spirits or the devil – especially women who were burned as witches!

Weaknesses:

- Myth of the chemical imbalance: Psychiatric drugs have often been prescribed to patients on the basis that they cure a ‘chemical imbalance.’Although scientists have been testing the chemical imbalance theory’s validity for over 40 years–and despite literally thousands of studies–there is still not one piece of direct evidence proving the theory correct.

- The treatments have serious side effects; for example, ECT can cause memory loss, and they are not always effective. Drugs may not “cure” the condition but simply act as a chemical straitjacket.

- The failure to find convincing physical causes for most mental illnesses must throw the validity of the medical model into question, for example, affective disorders and neuroses. For this reason, many mental disorders are called “functional.”The test case is schizophrenia, but even here, genetic or neurochemical explanations are inconclusive. The medical model is therefore focused on physical causes and largely ignores environmental or psychological causes.

- There are also ethical issues in labeling someone mentally ill – Szasz says that, apart from identified diseases of the brain, most so-called mental disorders are really problems of living. Labeling can lead to discrimination and loss of rights.

- The medical model has been the one that has been most influential in determining the way that mentally disturbed people are treated, but most psychologists would say that, at best, it only provides a partial explanation and may even be totally inappropriate.

- There are no known biological causes for any of the psychiatric disorders apart from dementia and some rare chromosomal disorders. Consequently, there are no biological tests such as blood tests or brain scans that can be used to provide independent objective data in support of any psychiatric diagnosis. Click here for more info.

- The reliability of diagnosing mental disorders has not improved in 30 years (Aboraya et al., 2006).

- Psychiatric diagnostic manuals such as the DSM and ICD (chapter 5) are not works of objective science but rather works of culture since they have largely been developed through clinical consensus and voting.

Their validity and clinical utility are therefore highly questionable, yet their influence has contributed to an expansive medicalization of human experience. Click here for more info

References

Aboraya, A., Rankin, E., France, C., El-Missiry, A., & John, C. (2006). The reliability of psychiatric diagnosis revisited: The clinician’s guide to improve the reliability of psychiatric diagnosis. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 3(1), 41.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

Breggin, P. R. (1979). Electroshock, Its Brain-disabling Effects. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Cuthbert, B. N., & Kozak, M. J. (2013). Constructing constructs for psychopathology: the NIMH research domain criteria. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(3), 928–937.

Fisher, A. J., Medaglia, J. D., & Jeronimus, B. F. (2018). Lack of group-to-individual generalizability is a threat to human subjects research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(27), E6106-E6115.

Fried, E. I., & Nesse, R. M. (2015). Depression is not a consistent syndrome: An investigation of unique symptom patterns in the STAR*D study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 172, 96-102.

Haslam, N., McGrath, M. J., Viechtbauer, W., & Kuppens, P. (2020). Dimensions over categories: A meta-analysis of taxometric research. Psychological Medicine, 50(9), 1418-1432.

Insel, T., Cuthbert, B., Garvey, M., Heinssen, R., Pine, D. S., Quinn, K., Sanislow, C., & Wang, P. (2010). Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(7), 748-751.

Kotov, R., Krueger, R. F., Watson, D., Achenbach, T. M., Althoff, R. R., Bagby, R. M., Brown, T. A., Carpenter, W. T., Caspi, A., Clark, L. A., Eaton, N. R., Forbes, M. K., Forbush, K. T., Goldberg, D., Hasin, D., Hyman, S. E., Ivanova, M. Y., Lynam, D. R., Markon, K., … & Zimmerman, M. (2017). The hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(4), 454-477.

World Health Organization. (1992). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioral disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Moniz, E. (1935). Angiomes cérébraux. Importance de l’angiographie cérébrale dans leur diagnostic. Bull. Acad. Méd.(Paris), 3, 113.

Regier, D. A., Narrow, W. E., Clarke, D. E., Kraemer, H. C., Kuramoto, S. J., Kuhl, E. A., & Kupfer, D. J. (2013). DSM-5 field trials in the United States and Canada, Part II: test-retest reliability of selected categorical diagnoses. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(1), 59-70.

Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179(4070), 250-258.

Van Putten, T., May, P. R., Marder, S. R., & Wittmann, L. A. (1981). Subjective response to antipsychotic drugs. Archives of General Psychiatry, 38(2), 187-190.