On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- The Montessori method of education is a non-traditional approach to learning that focuses on fostering a sense of independence and personal development in the classroom. Some of its unique components include three-hour time blocks for activities, mixed-age classrooms, and specific learning materials and curricula.

- This educational philosophy was created by Maria Montessori, an Italian physician and educator who strengthened her views on education while working in Rome in the late 1890s with developmentally delayed children.

- Many incredibly talented individuals learned and grew with the Montessori method. These individuals have gone on to be hugely successful in a wide range of disciplines, from politics to the tech industry, to the arts.

- Famous Montessori graduates include Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon.com; Sergey Brin and Larry Page, co-founders of Google; Anne Frank, World War II diarist; Prince William and Prince Harry, sons of Charles, Prince of Wales; George Clooney, Academy-award winning actor; Chelsea Clinton, daughter of Bill and Hillary Clinton.

- Although there are many benefits to the Montessori method and several empirical studies reveal promising results, there are some downsides to this type of education, such as expensiveness and lack of structure. Nevertheless, there are still tens of thousands of Montessori programs all over the world.

The Montessori method of education, named after its founder Maria Montessori, is an approach to classroom learning that emphasizes independence and choice.

This theory of teaching understands that children have an innate interest to learn and will be able to do so in a suitable environment. It strives to create a classroom that is filled with order, cleanliness, beauty, and harmony.

Contrary to the goal of most educational settings, which is to have its students reach maximum achievement in certain academic subjects, the Montessori method creates an environment that promotes a child’s optimal intellectual, physical, emotional, and social development to occur.

A Montessori classroom will definitely look different from what you may envision a normal learning environment to look like.

Nevertheless, there are many benefits to this approach to education, and Montessori schools still exist all around the world more than a century after the first classroom was created.

Historical Background

Maria Montessori was born on August 31st, 1870 to Alessandro Montessori and Renilde Stoppani. At 20 years old, she graduated from the Regio Istituto Tecnico Leonardo in Rome with a certificate in physics-mathematics and decided to go on to study medicine.

Although met with many challenges because of her gender, Montessori graduated from the University of Rome in 1896 as a Doctor of Medicine (Kramer, 2017). She then went on to work with children who were developmentally delayed at the University’s psychiatric clinic.

As part of her work, Montessori visited Rome’s mental asylums and observed that these children were in need of more stimulation.

It was during this time that she began to form her own educational philosophy. She began to attend courses in pedagogy and studied educational theory (Kramer, 2017).

Turn of the 20th Century: The Birth of the Montessori Method in Rome

In 1900, Montessori became co-director of the Scuola Magistrale Ortofrenica, a school for training teachers in educating mentally disabled children.

During her two years here, she developed certain materials and methods that would later serve as the backbone for her educational theory (Kramer, 2017).

Montessori continued to engage in academia, constantly reading and writing and ultimately earning a degree in philosophy from the University of Rome. She decided to modify her educational method to suit all individuals, regardless of their developmental ability.

On January 6th, 1907, she opened her first classroom, the Casa dei Bambini, or Children’s House, in an apartment building for low-income families in Rome. When the school first opened, 50 to 60 children ages two to seven were enrolled (Kramer, 2017).

The initial classroom was equipped with a table, blackboard, stove, chairs, and tables. The children engaged in activities such as dressing, dusting, and gardening, and they also used different classroom materials.

Montessori observed how free choice allowed the students to develop a deep sense of interest in the activities they engaged in, independent of any extrinsic rewards.

These promising observations fueled its further development and allowed it to spread throughout the world (Kramer, 2017).

Montessori Meets America, and Tensions Arise

Before reaching the U.S. in 1912, Montessori’s method spread throughout Italy and gained recognition in France, Switzerland, and the U.K.

There were also plans to open these schools in Argentina, China, Mexico, New Zealand, and more countries across the globe (Kramer, 2017).

The Montessori method became widely known in the U.S. after it was published in a series of articles in McClure’s Magazine.

In 1913, the Scarborough School in Maine became the first Montessori school to be established in the U.S. And just this same year, more than 100 Montessori schools were created in the U.S.

In December, Montessori herself traveled to the states for a three-week lecture tour during which she engaged in many positive conversations about this new theory of education (Kramer, 2017).

However, the feedback Montessori received was not all encouraging. In 1914, progressive educator William Heard Kirkpatrick and educational reformer John Dewey wrote a book titled The Montessori System Examined that greatly criticized this approach.

Additionally, the National Kindergarten Association was extremely dismissive of Montessori’s method, arguing that it was outdated, too rigid, required too much sense-training, and left too little room for imagination and social interaction.

Further, the way teachers were trained and the way materials were used was also a major source of conflict. Together, these dismissive attitudes push back on Montessori’s years of research and observation, but her classroom model is still used today.

Montessori Method of Teaching

The Montessori method of teaching is a child-centered educational approach based on scientific observations of children from birth to adulthood.

Developed by Dr. Maria Montessori, it values the human spirit and the development of the whole child—physical, social, emotional, and cognitive.

It emphasizes self-directed activity, hands-on learning, and collaborative play. In Montessori classrooms, children make creative choices in their learning while the classroom and teacher guide and facilitate the process.

Students learn through working with specially designed materials rather than direct instruction.

A Montessori classroom is different from the traditional school classroom. From the materials used to the way class time is divided, this classroom looks very different from a conventional learning environment.

Learning Materials

In terms of the specific learning materials, the Montessori method relies on certain types of materials, and they differ depending on the student’s age.

For the youngest student, the first materials will tend to be those that provide real-world skills, such as using scissors and other utensils, washing dishes, gardening, and more.

Gaining these skills helps to develop fine motor skills and hand-eye coordination and also begins to expose the child to the process of selecting, setting up, completing, and cleaning up an activity (Marshall, 2017).

The next set of materials that are introduced to the student are sensorial materials that help develop and strengthen the five senses. For example, a child might be tasked with pairing cylinders with the same sounds together.

An important part of the sensorial materials is that they only incorporate one sense – there is nothing else to distract or further inform the child (for example, the cylinders that have the same sound would not be colored the same; Marshall, 2017).

Once the child has mastered both basic fine motor and sensorial skills, they will transition into traditional academic subjects. In the literacy curriculum, students are taught phonics, the fine motor skills of writing (the way to grip the pencil and write letters), and how to write before they learn to read (Marshall, 2017).

For mathematics, children first learn single-digit numbers and what they mean, and then they begin to learn larger quantities and fractions. The student will then learn the order of operations (Marshall, 2017).

All subjects in the academic curriculum are introduced with concrete materials. The goal is to have the child learn through movement and gain an understanding of concrete concepts before moving on to more abstract ones (Marshall, 2017).

Engaging with the Learning Materials

Just as the learning materials themselves are specific to the Montessori method, the ways in which students are to engage with these materials are unique.

Montessori observed that children are capable of focusing for extended periods of time if they are working on activities that capture their spontaneous interest (Montessori, 1986).

In order to promote this spontaneous interest, Montessori emphasizes two key factors. The first is creating a cycle of work, referred to as the “internal work cycle.”

A child will be given the freedom to engage with a certain activity for as much interrupted time as they desire, so long as they set up the material and put it away afterward.

When they are done, they can move on to another activity. For example, a child might choose to play with Legos, so they must find sufficient space in the classroom, take out the Legos, play for as long as they want, and then clean up the Legos before moving on to something else (Cossentino, 2006).

But how long does this internal work cycle last?

In the typical Montessori setting, children work with these learning materials on their own or in small groups during a three-hour work cycle. This work cycle is referred to as the “external work cycle.”

During this time, they are given the freedom to choose what they work on, where they work, with whom they work, and how long they spend on each activity. The role of the teacher is to merely guide the children, helping those who are struggling with selecting materials or introducing new materials to children who are ready for them.

Ultimately, however, what the student does and learns as a result is entirely up to them. Because of the way this classroom is structured, there is very little competition between students, and there are no extrinsic rewards such as grades and tests to mark achievement (Cossentino, 2006).

Classroom Size

Another feature of the Montessori classroom that sets it apart is the age of the students. A typical classroom is composed of one, maybe two, different ages, most commonly separated by the year in which the students were born.

However, the Montessori classroom incorporates multiple different age groups who all learn together. This method of teaching recognizes the benefit of creating a family of learners to foster better social and academic schools.

This design allows older children to serve as mentors and develop leadership skills and provides younger students with the opportunity to learn from their peers rather than adults (Marshall, 2017).

For example, a classroom might have young children ages 3-6 in one classroom or an elementary school classroom of ages 6-9 altogether.

Montessori classrooms include students through the high school level, with an 18-year-old student being the oldest to learn in this type of educational environment.

It is clear that the Montessori classroom does not mirror a normal classroom environment.

And although the way learning is structured might raise some eyebrows, this method of education is the product of years of research and hands-on observation dating back more than a century ago.

Montessori’s Theory of Child Development

As someone who devoted her life to studying and observing children, Montessori devised her own theory of child development that greatly informed the Montessori method of teaching.

By identifying different stages of development, she was able to best determine what the optimal classroom environment should look like for different age groups.

The two key principles on which Montessori’s concept of child development was founded are that:

- Children and adults engage in self-construction (representing one’s own identity) by interacting with their environment;

- children have an innate path of psychological development.

The first principle motivated Montessori to really value both the way the physical classroom was organized and the specific materials she used for different age groups.

She believed that engaging in self-directed activities in a carefully structured environment can greatly foster self-construction and help a student reach their full potential.

The second principle informed Montessori’s view that all children would follow relatively similar trajectories of development, justifying the universality of her educational philosophy (Marshall, 2017).

Montessori argued that all children pass through sensitive periods for learning and that each stage provides a window of opportunity for the child to develop a particular set of skills.

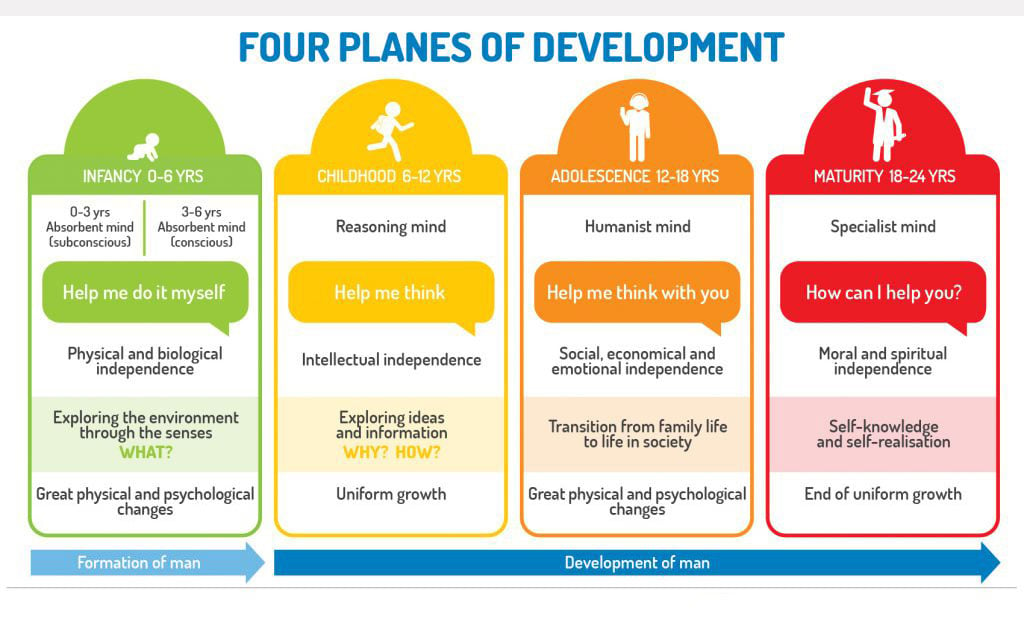

She identified four distinct planes of development each marked with different characteristics and learning modes:

First plane

The first plane encompasses those aged 0-6 and is marked by significant development. A child in this stage of development is a sensorial explorer, navigating the concrete environment and refining the five senses.

During this period of growth, a child first acquires language and gains an interest in small objects.

Another key feature of this plane is what Montessori called “normalization,” the process by which concentration and spontaneous discipline arise – two key requirements of Montessori’s method of education (Marshall, 2017).

Second place

The second plane includes individuals aged 6-12 and is characterized by the formation of a herd instinct in which children are more naturally inclined to work in a group setting as opposed to individually.

This is an important period for fostering socialization. Additionally, the second plane marks the beginning of intellectual independence, defined as thinking for yourself and actively seeking out new knowledge (and enjoying doing so).

The second plane of development is also the period in which children begin to formulate their moral sense and transition to slightly more abstract ways of thinking (Marshall, 2017).

Third plane

A child in the third plane of development is between the ages of 12 and 18 years old. In terms of physical development, this stage equates to puberty. Although much of the Montessori method focuses on strengthening a child’s ability to concentrate, Montessori recognizes that difficulties in concentration arise during adolescence.

This phase is also distinguished by the initial construction of the adult self, and another key feature is valorization – the need for external recognition of work.

An individual in their teenage years will desire commendation for their work, whether through the form of praise, good grades, or tangible rewards (Montessori, 1994).

Fourth plane

The fourth and final plane of development includes people aged 18-24 years old. Here, the individual fully embraces their studies and learns to lead society.

Economic independence is also a critical feature of this phase, as the adult now begin to support themself financially and begin to live a true life of independence (Montessori, 1994).

Together, these four planes not only illustrate most individuals’ developmental pathways but they largely inspired the Montessori method of education.

Montessori Classrooms by Age

Given the degree of specificity with which Maria Montessori designed her classrooms and her four different planes of development, it makes sense that the classrooms would look different depending on age. This section will dive into the different educational practices for each age group.

Toddler Programs

Those who are under three years of age will learn in a classroom that provides opportunities to develop movement and independence (including potty training) and that emphasizes materials and activities that are scaled to that child’s size and skill level.

Within the toddler programs, Montessori splits this age group into two smaller groups. A “nido” (Italian for nest) serves those who are under fourteen months, and a “Young Child Community” is for those who are roughly 1-3 years old (“North American Montessori Center,” n.d.).

In some of these schools, parents are present and actively participate with their children. This is very common given the child’s young age and attachment to their parents.

It can be difficult for children to separate from their mother or father, especially in unknown environments (“North American Montessori Center,” n.d.).

Preschool and Kindergarten

Children 3-6 years old will attend school at what’s called a Children’s House. Each classroom will have about 20-30 students of mixed ages and a full team of teachers (both a lead and an assistant).

Classrooms have small tables arranged individually and in clusters so as to allow both independent learning as well as opportunities for social interaction.

The learning materials are placed on shelves throughout the classroom, and a teacher will typically first introduce the activities and then the children can choose what to do and for how long.

For this age group, practical activities will include pouring liquids, washing tables, and sweeping. Academic activities for math, language, music, art, and culture are also very hands-on and emphasize developing the senses through requiring the student to rely on multiple senses (for example, both sight and touch) during a single activity.

Some examples include sandpaper letters for learning to write and strings of beads for learning basic arithmetic (“North American Montessori Center,” n.d.).

Elementary Classrooms

Montessori elementary-level classrooms are usually composed of either 6 to 9-year-old children, 9 to 12-year-old children, or 6 to 12-year-old children.

In terms of the structure, teachers will first present lessons to groups of children but they are then given the opportunity to freely explore and further learn.

At the beginning of the school year, teachers commonly deliver “great lessons” which introduce students to the interdisciplinary nature of learning that exposes students to new areas of exploration.

Another key feature of learning at this developmental stage is acquiring knowledge and investigating outside of the classroom.

Because Montessori is a firm believer in people’s innate interest in learning, she greatly encourages children of all ages to continue their intellectual exploration beyond the walls of the classroom (“North American Montessori Center,” n.d.).

Middle and High School

In the first year that Montessori schools were established, more than 100 separate institutions were created. Today, thousands of Montessori schools exist all over the world, even in the U.S., where this method was and still is highly criticized.

Since the creation of the Scarborough School in 1913, there are many similar institutions that demonstrate the long-lasting legacy of Montessori.

Modern Day Examples

Haven Montessori Charter School

The Haven Montessori Charter School was founded in 2003 by Elisa McKnight. Located in Flagstaff, Arizona, this school offers both part and full-time schedules for children from 4 months through 6th grade.

All of the teachers are trained to follow the Montessori method, and the school strives to produce a rich and nurturing environment for students in order to inspire peaceful relations and a love of learning (“About Haven Montessori School,” 2020).

Dixon Montessori Charter School

The Dixon Montessori Charter School (DMCS) in Dixon, California, strives to inspire its students to achieve their individual greatest potential in a nurturing environment that emphasizes discovery, academic excellence, and positive social contribution.

Inspired by one of Maria Montessori’s main principles that children have an innate passion for learning, the school’s motto is “igniting the love of learning.”

The school serves students from transitional kindergarten all the way through 8th grade, and in order to fulfill the values brought forth by Montessori, DMCS relies on low teacher-to-student ratios, family participation, multi-age classrooms, a diverse curriculum, and differentiated learning for each student (“Dixon Montessori Charter School,” n.d.).

Inner Sydney Montessori School

Inner Sydney Montessori School (ISMS) is a dual-campus early learning and primary day school located in the Balmain, Lilyfield, and Rozelle suburbs of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

The school was founded in 1981 by a group of parents living in the inner city areas of Sydney. The school serves up to 300 students from 3-12 years old and an additional 100 families in the 0-3 program (“Inner Sydney Montessori School,” n.d.).

The largest campus in Balmain has an infant community, three preschool classes for 3 to 6-year-olds, and seven primary classes for children aged 6-9 or 9-12 years old. The classrooms overlook leafy play areas and are large and bright.

The school also has certain outdoor play areas and also utilizes the nearby park for lunchtime. The Lilyfield campus has two pre-primary classes for children aged 3-6, and the Rozelle campus supports the infant community (“Inner Sydney Montessori School,” n.d.).

ISMS is the largest Montessori school in all of Sydney and has a wide variety of academic opportunities alongside drama, art, music, Spanish, and sports enrichment lessons with in-house staff (“Inner Sydney Montessori School,” n.d.).

Kamala Niketan School

The Kamala Niketan School in Tiruchirappalli, India, was founded by Geetanjali Satyamoorthy in 1991 and began as a play school for 30 children. Today, it serves roughly 4,020 students over a 6.5-acre plot of land and has more than 60 classrooms and labs.

The school strives to have students reach their full potential, gain strong physical, creative, and communication skills, and develop confidence as individuals.

The school’s motto is “Fluorescence, Flame, Fortitude” to signify the blossoming of an individual, the intensity of thought, and the patience and strength of mind that is required of any student (“Kamala Niketan School,” n.d.).

These examples help demonstrate the popularity and widespread nature of the Montessori schools. These schools are located all over the world but are united by the same educational mission.

Empirical Research

The Montessori method is not only a globally popular approach to education, but it has also produced some of the world’s most successful leaders.

And while it seems doubtful that this approach wouldn’t be deemed successful from an empirical standpoint, it is still useful to critically examine this method so as to increase its credibility.

While there are certainly several studies that have tackled the question of the effectiveness of the Montessori method, many of these studies have methodological flaws.

These studies typically have no randomized control trials, small sample sizes, have too many confounding variables, which make it hard to conclude that being in a Montessori classroom is what’s leading to the observed outcomes, and very few are longitudinal in design.

Additionally, even for those studies that do demonstrate effectiveness to a certain degree, it is hard to know what exactly about the Montessori method is effective since there are so many different components that make this philosophy unique.

That being said, there is still merit in considering the empirical research that has been done, and the conclusions are of value.

- A 2017 meta-analysis found that the various methods (such as a focus on sensorial development and teaching literacy through phonics) are generally effective (Marshall, 2017).

The most notable study on this topic examined children in Montessori and non-Montessori education in two separate age groups – 5 and 12-year-olds – on a variety of cognitive, academic, social, and behavioral measures.

For the 5-year-olds, the researchers found significant group differences in academic and social skills, executive functioning, and theory of mind. For the 12-year-olds, there were significant group differences in measures of story writing and social skills.

Additionally, when asked as part of a questionnaire, the Montessori group indicated that they felt a greater sense of community (Lillard & Else-Quest, 2006).

- Another study compared scores on math, science, English, and social studies tests several years after children had left the Montessori classrooms, revealing that the Montessori students scored significantly higher on math and science exams but no higher on the English and social studies exams.

This study demonstrates that the Montessori method might not be more effective across the board but that some learning materials and subjects are more effective than others (Dohrmann et al., 2007).

- Dating back a couple of decades to 1975, Louise Miller and colleagues administered a Stanford Binet Intelligence Scale every year over a four-year period from Pre-K to 2nd grade. The team found that those in a Montessori program had higher mean scores on this test.

- Although most empirical studies use academic achievement as a measure of effectiveness, a study done in France looked into the way the Montessori program impacts an individual’s creativity.

One hundred fifty-nine 7 to 12-year-olds were tested longitudinally on five different tasks that focused on divergent and integrative thinking. For both types of tasks at both time points, the Montessori children scored higher than those who went to a more conventional school (Besançon & Lubart, 2008).

- Despite these studies all proving to be promising, some research has indicated that the Montessori approach might not be as effective as some make it out to be.

For example, a 2005 study done in a Buffalo public Montessori magnet school was not able to support the hypothesis that a Montessori school was associated with higher academic achievement (Lopata et al., 2005).

Pros and Cons

Just as the literature suggests both upsides and downsides, there are also general pros and cons to the Montessori method.

The benefits of the Montessori method include the emphasis on fostering independence at a young age, more social interaction for the students, and an inclusive environment that incorporates multiple ages and is conducive to various learning styles and developmental pathways (Meinke, 2019).

On the downside, many Montessori programs are expensive, making them inaccessible to most families. Additionally, the lack of structure can serve as a challenge for younger children, who might need a sense of structure in order to reach their full potential (Meinke, 2019).

The Montessori method of education strives to provide students with the support and materials they need to blossom. This approach places significant emphasis on independence and freedom of choice within the classroom, differentiating it from more traditional methods of teaching.

The Montessori philosophy has its own unique curriculum that targets mixed-age groups of students. And while there are many criticisms of this theory, roughly 20,000 Montessori programs exist today all around the world.

FAQs

What is Montessori education?

Montessori education is a child-centered approach that encourages self-directed learning through hands-on activities and collaborative play.

Developed by Dr. Maria Montessori, it nurtures the whole child – physically, socially, emotionally, and cognitively, emphasizing independence and respect for a child’s natural psychological development.

How do, according to Montessori, the environment and freedom of a child play a significant role in his education?

According to Montessori, the child’s environment and freedom are crucial for their education. The environment should be prepared to encourage exploration, creativity, and independence.

It should be child-centered, with materials and activities suitable for the child’s developmental stage.

Freedom is essential as it allows the child to learn at their own pace and follow their interests. This encourages intrinsic motivation and responsibility and helps develop self-discipline and problem-solving skills.

How does Montessori education foster creativity and critical thinking?

Montessori education fosters creativity and critical thinking by providing children with an environment that encourages exploration, problem-solving, and independent thinking. Through the use of hands-on materials, students are given the freedom to explore, make choices, and pursue their interests.

This approach promotes creativity as children engage in open-ended activities and self-expression. Additionally, Montessori classrooms encourage children to think critically by presenting them with real-world problems and allowing them to find their own solutions, promoting analytical thinking and decision-making skills.

References

About Haven Montessori School. (2020). Retrieved from https://havenmontessori.org/about/

Besançon, M., & Lubart, T. (2008). Differences in the development of creative competencies in children schooled in diverse learning environments. Learning and individual differences, 18 (4), 381-389.

Cossentino, J. M. (2006). Big work: Goodness, vocation, and engagement in the Montessori method. Curriculum Inquiry, 36 (1), 63-92.

Dixon Montessori Charter School. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.dixonmontessori.org/about-our-school.html

Dohrmann, K. R., Nishida, T. K., Gartner, A., Lipsky, D. K., & Grimm, K. J. (2007). High school outcomes for students in a public Montessori program. Journal of research in childhood education, 22 (2), 205-217.

Inner Sydney Montessori School. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.isms.nsw.edu.au/about-our-school/school-history/

Kamala Niketan School. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.kamalaniketan.com/

Kilpatrick, W. H. (1914). The Montessori system examined. Houghton Mifflin.

Kramer, R. (2017). Maria Montessori: a biography. Diversion Books.

Lillard, A., & Else-Quest, N. (2006). The early years: Evaluating Montessori education. Science, 313(5795), 1893-1894.

Lopata, C., Wallace, N. V., & Finn, K. V. (2005). Comparison of academic achievement between Montessori and traditional education programs. Journal of research in childhood education, 20 (1), 5-13.

Marshall, C. (2017). Montessori education: a review of the evidence base. npj Science of Learning, 2(1), 1-9.

Meinke, H. (2019). Exploring the pros and cons of montessori education. Retrieved from https://www.rasmussen.edu/degrees/education/blog/pros_cons_montessori_education/

Miller, L. B., Dyer, J. L., Stevenson, H., & White, S. H. (1975). Four preschool programs: Their dimensions and effects. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 1-170.

Montessori, M. (1986). The Discovery of the child (5. izd.).

Montessori, M. (1994). From Childhood to Adolescence. 1948. Rev. ed. Trans. AM Joosten. Oxford, England: Clio.

North American Montessori Center. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.montessoritraining.net/