On This Page:

Reductionism in psychology refers to understanding complex behaviors and mental processes by breaking them down into simpler components or underlying factors, often focusing on biological or physiological mechanisms. It’s the belief that complex phenomena can be explained by examining simpler, foundational elements or causes.

Reductionists say that the best way to understand why we behave as we do is to look closely at the very simplest parts that make up our systems and use the simplest explanations to understand how they work.

What is Reductionism?

Reductionism operates on the principle of parsimony in science, suggesting that complex phenomena should be distilled down to their simplest foundational principles.

Advocates of reductionism contend that behaviors and mental processes are best elucidated through the lens of foundational sciences, such as physiology and chemistry.

Yet, almost any simplification of behavior can be labeled reductionist. The methodology employed in various psychological disciplines, like behaviorism, biology, and cognition, embodies a reductionist stance.

Such approaches inherently simplify intricate behaviors to a manageable set of variables to discern causality, aligning reductionism closely with determinism.

Reductionism manifests on a spectrum. At its most fundamental level, it provides physiological explanations, linking behaviors to neurochemicals, genes, and brain structures.

The opposition to reductionism is “holism,” which emphasizes the whole system rather than its individual components.

At the broadest end, the sociocultural perspective underscores how environment and upbringing shape behavior. Intermediate viewpoints encompass behavioral, cognitive, and social explanations.

Examples

Behaviorism

Behaviorism focuses on observable behaviors and disregards internal mental processes, reducing complex human behavior to stimuli and responses often influenced by environmental factors.

This approach simplifies behavior to measurable, observable events, overlooking the potential intricacies of cognition, emotions, and other internal states.

Behaviorism uses a reductionist vocabulary: stimulus, response, reinforcement, and punishment. These concepts alone are used to explain all behavior.

This is called environmental reductionism because it explains behavior in terms of simple building blocks of S-R (stimulus-response).

That complex behavior is a series of S-R chains. Behaviorists reduce the concept of the mind to behavioral components, i.e., stimulus-response links.

Biopsychology

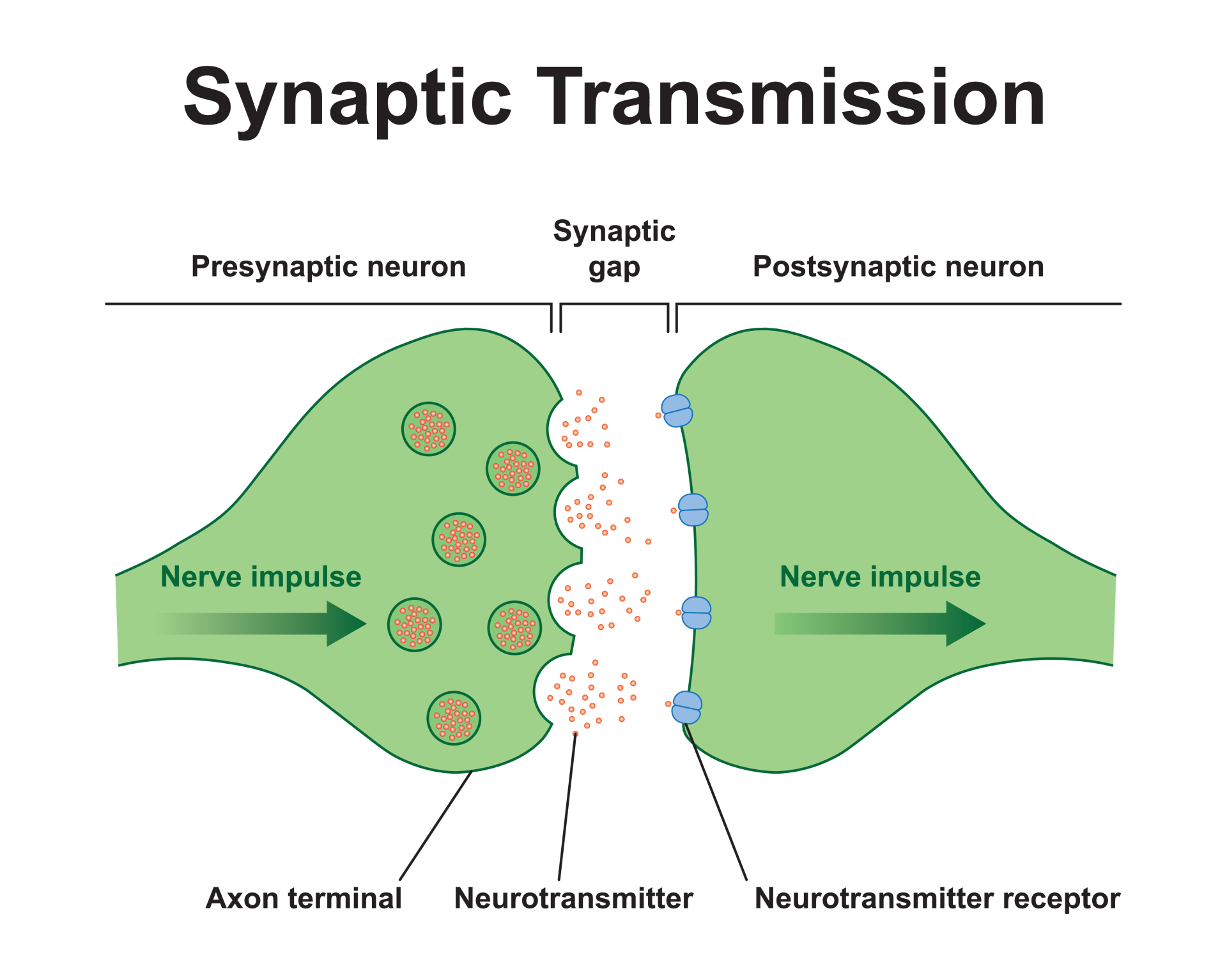

Biopsychology, also known as biological psychology or psychobiology, is often considered a reductionist approach as well. It seeks to explain psychological phenomena in terms of biological processes, such as brain activity, neurotransmitters, hormones, and genetic factors.

By attributing complex behaviors and mental states to underlying physiological and biological mechanisms, biopsychology simplifies these phenomena into more fundamental biological components.

While this approach provides valuable insights into the biological bases of behavior, critics argue it might overlook the complexities and interactions of psychological, social, and environmental factors.

Explanations for the cause of mental illnesses are often reductionist. Genetics and neurochemical imbalances are frequently highlighted as being the main cause of these disorders. In the case of schizophrenia, for example, excess production of the neurotransmitter dopamine is seen as a possible cause.

This view has implications for treatment. Gender can also be reduced to biological factors (e.g., hormones). Also, language can be reduced to structures in the brain, e.g., Broca’s Area and Wernicke’s area. Another example of biological reductionism is aggression – e.g., testosterone levels.

Structuralism

Structuralism, one of the earliest schools of psychology, is also considered a reductionist approach.

Founded by Wilhelm Wundt and further developed by his student Edward Titchener, structuralism aimed to understand the structure of the mind by analyzing its basic components.

It focused on introspection as a method, where trained observers would report their conscious experiences in response to specific stimuli.

Structuralists believed that by breaking down mental processes into their most basic elements, like sensations and feelings, they could understand the overall structure of human consciousness. In essence, they aimed to reduce complex cognitive experiences to simpler constituent parts.

Wundt tried to break conscious experiences down into their constituent (i.e., basic) parts: images, sensations, and feelings.

Critics of structuralism argued that introspection was subjective and that mental processes are too complex to be reduced to just a few components.

Cognitive psychology

Cognitive psychology, which focuses on understanding internal mental processes such as thinking, memory, perception, and problem-solving, is less reductionist compared to behaviorism or biopsychology. However, it still has elements of reductionism.

Cognitive psychology often breaks down complex mental processes into simpler components for study. For instance, memory can be divided into short-term, long-term, and sensory storage, and further, into processes like encoding, storage, and retrieval. Cognitive psychologists aim to grasp the broader function by understanding these basic components.

Yet, the cognitive approach generally recognizes the complexity and interactivity of mental processes. While it simplifies for the sake of study and understanding, it typically doesn’t reduce behavior or cognition to just one underlying factor or mechanism.

Instead, it aims to create models depicting various cognitive functions’ interplay and organization.

Machine reductionism

Cognitive psychology uses the principle of machine reductionism as a means to describe and explain behavior.

Machine reductionism refers to the idea of viewing organisms, including humans, as machine-like entities where complex systems and behaviors can be understood by breaking them down into their individual parts, much like the components of a machine.

It’s a type of reductionism prevalent in certain domains of biology, neuroscience, and even some areas of psychology.

Psychodynamic approach

When viewed in terms of reductionism, the psychodynamic approach can be both reductionist and holistic.

On the one hand, it might be deemed reductionist because it often attributes complex behaviors and mental states to a few underlying unconscious drives and conflicts, especially those related to sexuality and aggression. For instance, a phobia might be interpreted as a displaced childhood fear.

On the other hand, the approach is also holistic as it considers the entirety of an individual’s life experiences, especially their early developmental stages, and sees behaviors as a result of intricate internal processes and conflicts.

It doesn’t just look at the behavior itself but dives deep into the underlying psychological forces that drive it.

Strengths

The use of a reductionist approach to behavior can be a useful one in allowing scientific study to be carried out. Scientific study requires the isolation of variables to make it possible to identify the causes of behavior.

Breaking complicated behaviors down into small parts means that they can be scientifically tested. Then, over time, explanations based on scientific evidence will emerge.

For example, research into the genetic basis of mental disorders has enabled researchers to identify specific genes believed to be responsible for schizophrenia.

This way, a reductionist approach enables the scientific causes of behavior to be identified and advances the possibility of scientific study.

A reductionist approach to studying mental disorders has led to the development of effective chemical treatments.

However, some would argue that the reductionist view lacks validity .

For instance, we can see how the brain responds to particular musical sounds by viewing it in a scanner, but how you feel when you hear certain pieces of music is not something a scanner can ever reveal.

Just because a part of the brain that is connected with fear is activated while listening to a piece of music does not necessarily mean that you feel afraid.

In this case, being reductionist is not a valid way of measuring feelings.

Limitations

It can be argued that reductionist approaches do not allow us to identify why behaviors happen.

For example, they can explain that running away from a large dog was made possible by our fear centers, causing a stress response to better to allow us to run fast, but the same reductionist view cannot say why we were afraid of the dog in the first place.

In effect, by being reductionist, we may be asking smaller, more specific questions and, therefore, not addressing the bigger issue of why we behave as we do.

It has been suggested that the usefulness of reductionist approaches depends on the purpose to which they are put.

For example, investigating brain response to faces might reveal much about how we recognize faces, but this level of description should not perhaps be used to explain human attraction.

Likewise, whilst we need to understand the biology of mental disorders, we may not fully understand the disorder without taking into account of social factors which influence it.

Thus, whilst reductionism is useful, it can lead to incomplete explanations.

Interactionism is an alternative approach to reductionism, focusing on how different levels of analysis interact with one another.

It differs from reductionism since an interactionism approach would not try to understand behavior from explanations at one level but as an interaction between different levels.

So, for example, we might better understand a mental disorder such as depression by bringing together explanations from physiological, cognitive, and sociocultural levels.

Such an approach might usefully explain the success of drug therapies in treating the disorder, why people with depression think differently about themselves and the world, and why depression occurs more frequently in particular populations.