Key Takeaways

- Both psychopathy and sociopathy (also referred to as antisocial personality disorder or ASPD) are characterized by a pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others.

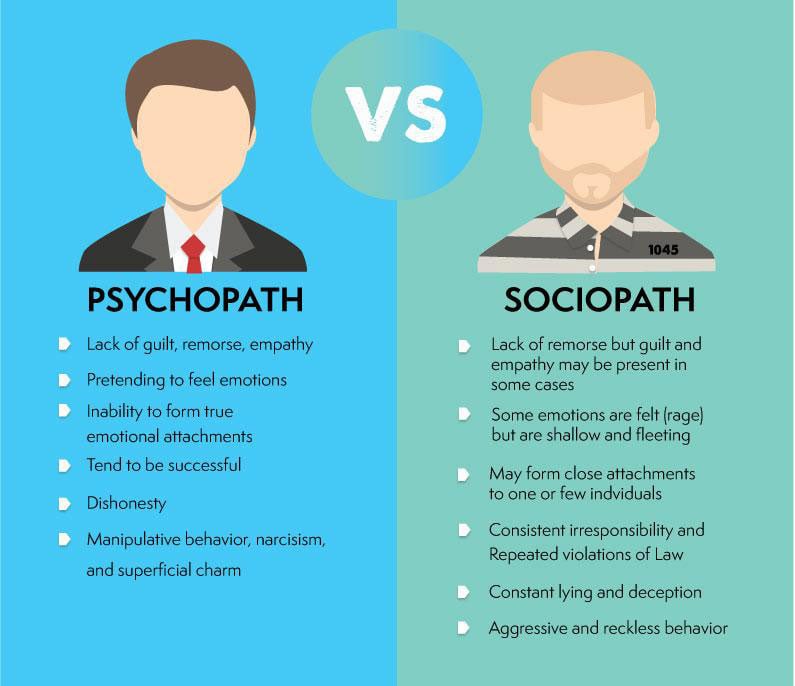

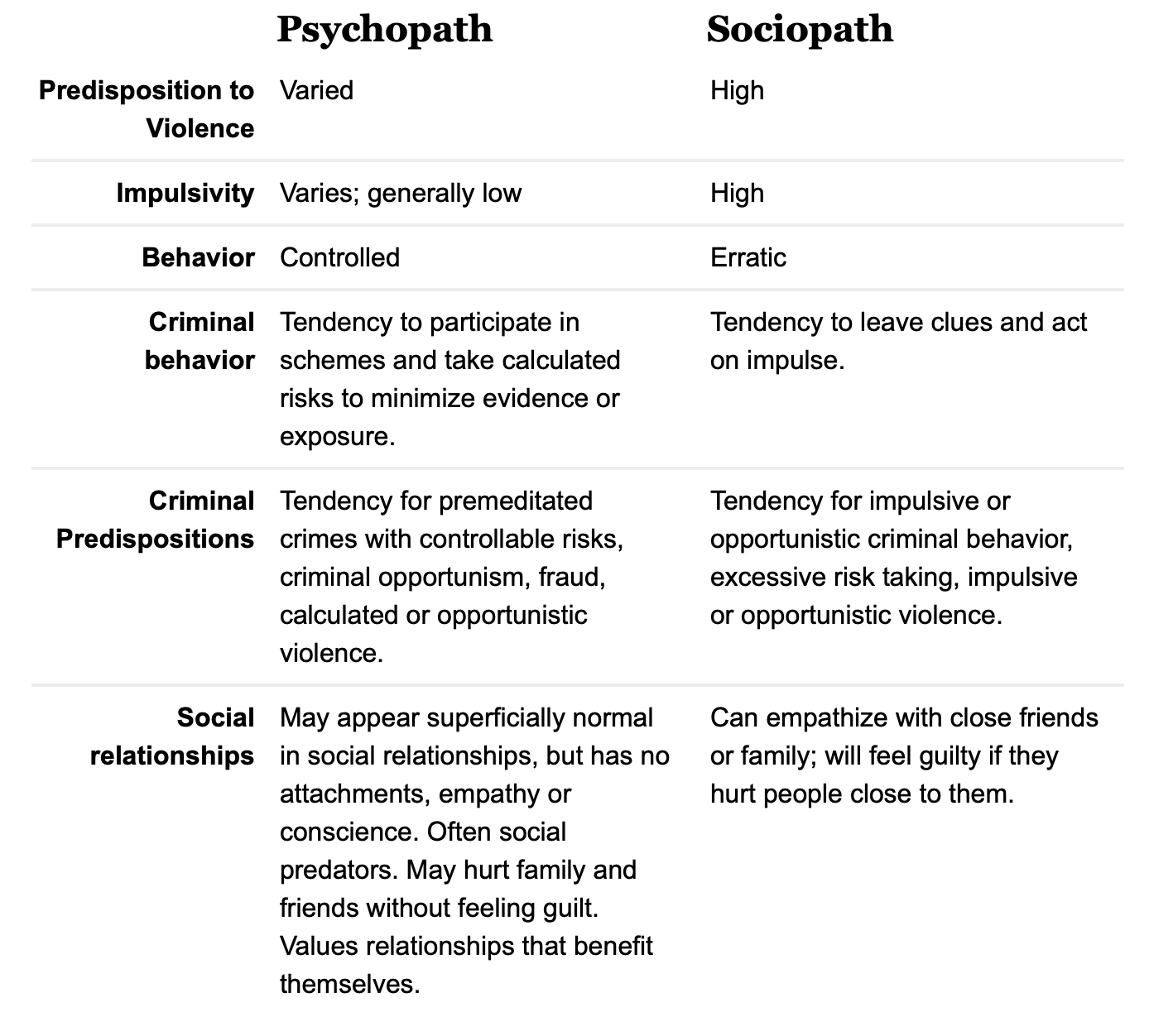

- A sociopath is a person with a personality disorder that is marked by traits of impulsivity, risk-taking, and violence. A psychopath is a person who has an antisocial personality disorder characterized by a lack of regard for the rights and feelings of others, controlled and manipulative behavior, the absence of shame, and an inability to form emotional relationships.

- Deceit and manipulation are central aspects of both personality types. However, even though they are often confused with one another because they manifest in similar ways, these are two distinct forms of personality disorders.

- Although the lifetime prevalence of both disorders is roughly 1%, because of violent acts associated with and society’s fascination with this disorder, they are often the protagonist of a film or the headline of a newspaper.

- In addition to the unique ways in which these two disorders are diagnosed, their unique histories, and the different treatment approaches, the key difference between the two is that psychopathy has an affective and interpersonal domain that is not related to ASPD.

Difference Between Psychopath vs. Sociopath

Although sociopathy and psychopathy can manifest in very similar ways, it’s important to understand that these diagnoses are not interchangeable.

And while the average layperson will often label any serial killer or someone who engages in heinous acts of violence as having one of these two disorders, not all violent people are psychopaths or sociopaths.

Aside from the differences in the ways these two are diagnosed, their unique histories, and the different methods used to treat these disorders, the key distinction is that psychopathy possesses a unique affective and interpersonal domain that is not related to sociopathy.

Both disorders have an antisocial/deviance domain, but characteristics such as shallowness, callousness, lack of empathy, and emotional detachment are uniquely psychopathic traits.

Both psychopathy and sociopathy (now referred to as antisocial personality disorder, or ASPD) are classified as personality disorders. But what are personality disorders? Personality is what makes you who are, so how can that be disordered?

What Is A Psychopath?

- Individuals with psychopathy (Antisocial Personality Disorder) display a decrease in emotional response and lack of empathy with others.

- This individual might possess a superficial charm but, deep down, is manipulative and impulsive.

- A psychopath is characterized by a lack of regard for the rights and feelings of others, controlled and manipulative behavior, the absence of shame, and an inability to form emotional relationships (Morin, 2021).

- They are incapable of loyalty to individuals, groups, or social values. They are grossly selfish, callous, irresponsible, impulsive, and unable to feel guilt or to learn from experience.

Psychopathy is extremely uncommon – it is estimated that only 0.5-1% of the population meets the criteria for this disorder (Wynn et al., 2012).

It is even less common among women. One study found that 11% of female violent subjects are psychopaths but 31% of male violent subjects can be accurately labeled with this disorder (Grann, 2000).

Additionally, while as high as 20-25% of the prison population qualifies for the diagnosis (Wynn et al., 2012), only 16% of females who are incarcerated meet the criteria for psychopathy (Salekin et al., 1997).

But these statistics have not always been common knowledge, or even knowledge at all for that matter. When was psychopathy first studied, and how has our understanding of this disorder evolved?

The Origin of Psychopathy

From Medea to King Shahryar in The Book of One Thousand and One Nights, psychopathy has always existed in historical myths and stories (Kiehl & Hoffman, 2011).

Academic writing about this disorder dates back all the way to ancient Greece, when one of Aristotle’s students, Theophrastus, was possibly the first to write about psychopaths, labeling them as “the unscrupulous” (Millon et al., 1998). Put simply, Theophrastus was describing people without empathy or a conscience.

Centuries and centuries later, one of the first medical professionals to describe psychopaths was French doctor Phillipe Pinel. In 1806, Pinel called this condition “maniaque sans délire,” or insanity without delirium. One of his students, Jean Etienne Dominique Esquirol, called it “la folie raisonnante,” or rational madness (Guggenbühl-Craig, 1999).

Another popular term that was used in the U.S. and England throughout the 19th and early 20th century was “moral insanity” (Prichard, 1837). While different and certainly not terms that would be accepted today, these terms all create an image of a psychopath as someone who is insane or mad.

But how did the word psychopath come about? In 1888, German psychiatrist J.L.A. Koch was credited with being the first to use the term “psychopastiche” (psychopathic in German), meaning suffering soul (Hervé, 2007).

At the turn of the 20th century, the diagnostic criteria for psychopathy began to take shape and evolve.

Although it was first defined as a lack of a moral core, the so-called Germany School of Psychopathy expanded the diagnosis to incorporate people who hurt themselves and others (Kiehl & Hoffman, 2011).

When the Great Depression hit in the late 1920s, psychiatry was using the word psychopath to include people who were depressed, shy, and insecure. Generally speaking, the term was used to label anyone who was deemed abnormal (Kiehl & Hoffman, 2011).

Beginning in the late 1930s and transitioning into the early 1940s, two academic works of literature were published. The first was Psychopathic States by Scottish psychiatrist David Henderson, which focused on his observations of a psychopath as someone who, in many ways, is perfectly rational and capable of achieving egocentric goals (Henderson, 1942).

Two years later, American psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley published his famous Mask of Sanity. Cleckley describes clinical interviews he had with patients who were in a locked institution and outlines basic traits he associates with psychopathy (Cleckley, 1951).

The title refers to the normal “mask” that conceals a person’s psychopathic tendencies. This work was instrumental to understanding this disorder and making the concept of psychopathy more concrete.

Jumping forward a decade, the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) was published in 1952 and grouped psychopathy under “Sociopathic Personality Disturbance.”

Affective and behavioral criteria were diagnosed separately as antisocial reaction and dissocial reaction. In 1968, the DSM-II joined these two together under the category of antisocial personality.

And in 1980, the DSM-III defined psychopathy as a persistent violation of social norms and dropped the affective traits altogether. Today, psychopathy is no longer part of the DSM, but ASPD, which we will discuss later, remains a part of this diagnostic manual.

Etiology

Similar to the causes of most mental disorders, the causes of psychopathy are not understood too well. Nevertheless, research has demonstrated that it is highly correlated with abnormal brain activity that is a product of both genetics and very early developmental problems.

In other words, both nature and nurture play a role in the development of psychopathy (Kiehl & Hoffman, 2011). Typically, an individual will have a genetic predisposition to psychopathy, and then a poor environment allows this disorder to manifest in their lives.

Specifically, research done by developmental psychologist Robert Kegan (1986) revealed that an abnormally slow rate of brain development causes psychopaths to be essentially frozen in time, such that they never grow out of the egocentricity, impulsiveness, and selfishness that marks adolescence.

How It Is Diagnosed

Accurately diagnosing an individual with psychopathy is an incredibly crucial task. Because this disorder is so highly stigmatized in society, especially within the media and popular culture, a positive diagnosis can come with an incredibly pejorative label.

In 1980, Canadian psychologist Robert Hare developed the Psychopathy Checklist (PCL), a universal tool that distilled the wide-ranging characteristics of this condition into a 20-item inventory.

Through administering a semi-structured interview and reviewing the client’s personal files, clinicians rely on the PCL to provide a reliable and valid measure of a construct that has direct implications for mental health and the criminal justice system.

The checklist distinguishes between two different diagnostic factors. Factor 1 describes affective criteria, and Factor 2 contains socially deviant criteria. The instrument requires clinicians to give a score on each of the 20 total items on a scale from 0 (item does not fit) to 2 (item definitely fits).

Thus, the minimum score is zero and the maximum score is 40. Hare defined psychopathy as a score of 30 or more, excluding most individuals with ASPD (since these individuals are less likely to exhibit interpersonal and affective traits).

In 2003, Hare revised the checklist and broke up the two factors into four (see more in the next section). This new tool, the PCL-R (R for revised), is used by clinicians today to diagnose psychopathy.

That same year, Hare co-authored the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version (PCL-YV) to assess psychopathic traits in youth (Forth, 2005).

Signs and Symptoms

As previously mentioned, Hare revised the original PCL to instead include four separate factors. These factors capture the key signs and symptoms of psychopathy and are as follows:

Factor 1: Interpersonal

Factor 2: Affective

- Lack of remorse or guilt

- Emotionally shallow

- Callous/lack of empathy

- Failure to accept responsibility for own actions

Factor 3: Lifestyle

- Need of stimulation/proneness to boredom

- Parasitic lifestyle

- Lack of realistic, long-term goals

- Impulsivity

- Irresponsibility

Factor 4: Antisocial

- Poor behavioral control

- Early behavioral problems

- Juvenile delinquency

- Revocation of conditional release

- Criminal versatility

Other: promiscuous sexual behavior and short-term marital relationship

Because the PCL-R is scored on a scale from 0-40, it is possible, and very likely, that an individual will exhibit a combination of traits from all four of these buckets.

And because these are 20 different items, it is also likely that two individuals who may be diagnosed with psychopathy will score very differently on each item. In other words, no two cases of psychopathy will look the same.

One individual might be a pathological liar in the corporate setting and another might live a parasitic lifestyle and be unable to maintain meaningful, emotional relationships.

Although there are several manifestations of psychopathy, a common duality among psychopaths is that of successful and unsuccessful psychopaths.

Successful Vs. Unsuccessful Psychopaths

A successful psychopath might sound like an oxymoron: how can a psychopath, someone who is generally depicted as violent and devoid of emotion, be successful?

Typically, an individual who is classified as a successful psychopath has intact neurological functioning, which helps them achieve their goals with more nonviolent methods (Gao & Raine, 2010).

Their amygdalas and prefrontal cortices have normal volumes, leading to better executive functioning and protecting them from conviction.

Generally speaking, these individuals are able to achieve marked societal success, whether it be through degrading employees, blaming others, or relying on deceptiveness, especially in the workplace (Mathieu et al., 2014).

In a study conducted by Cynthia Mathieu and colleagues, the researchers demonstrated ways in which successful psychopaths can affect the corporate workplace.

Specifically, they found that psychopathic qualities of bosses negatively impact employee performance and decrease their mood and well-being. They also detailed a direct relationship between an increased PCL-R score and employee distress and job satisfaction, such that a higher score predicts higher employee psychological distress and lower job satisfaction.

On the other hand, unsuccessful psychopaths are those whose brains and autonomic nervous systems have structural and functional impairments, causing more overt forms of offending, such as murder.

But there is definitely a gray area – this is not a clear-cut distinction. Serial killers are often labeled as “semi-successful” psychopaths because they often engage in smart, premeditated acts and can avoid the police for some time.

However, these acts are less subtle than that of a successful psychopath, so it is more likely that they will eventually be noticed (Gao & Raine, 2010).

Research on successful vs. unsuccessful psychopaths is not the only avenue for empirical findings. There also exists an abundance of research pertaining to genetics, brain development, and specific traits and signs.

Empirical Research

Because genetics is half of the nature plus nurture equation, researchers have looked into the genetic ties to psychopathy. Specifically, a study conducted on twins found that 50% of the variance in antisocial behavior is attributed to genetics.

Furthermore, the study identified 7 genes, such as 5HTT and BDNF, which are thought to influence brain structures and cause aggressive behavior. Another gene, MAOA, controls the production of a protein that breaks down brain-signaling chemicals, such as dopamine and serotonin and is thought to contribute to psychopathic behavior in individuals with a variant of this gene.

This variant, MAOA-L, produces less of the protein that breaks down these chemicals, causing such chemicals to build up and lead to impulsive behavior, mood swings, and violent tendencies (Raine, 2008).

In addition to the genetic component, research studies have also identified anatomical differences in people who meet the diagnostic criteria for psychopathy.

Both the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) are key players in fear conditioning, socialization, decision-making, and moral judgment, but individuals with psychopathy have been found to have reduced amygdala volume and a 22% reduction in VMPFC gray matter (Glenn et al., 2012).

Other research objectives have sought to debunk common misconceptions about psychopaths. One study found that contrary to popular belief, psychopaths can discern moral wrongs.

The researchers presented participants with 8 moral and 8 conventional stimuli and asked them to identify which 8 were morally wrong (in the absence of laws, rules, or customs). They found that those with psychopathy had a moral accuracy that was better than chance (Aharoni et al., 2012).

Another study found that psychopaths do, in fact, exhibit regret, but what distinguishes them from non-psychopaths is that they do not avoid regret during decision-making.

In other words, they do not use regret to guide their behavior, so they might make rash decisions without any consideration for future consequences (Baskin-Sommers, 2016).

This is by no means an exhaustive list of the research done on psychopaths. And although there has been an overwhelming body of research in this domain, so much is still unknown, especially with regard to treatment.

Treatment

It is hard to identify one treatment for psychopathy because there is not a clear cause and no two cases of psychopathy are identical. There is no one drug or one specific form of therapy that has been found to universally reduce the effects of this disorder.

As such, treatments must be unique – what works for some might not work for all. Regardless, treatment should aim to reduce substance abuse, remove the association with negative networks, and alter behavior.

A common approach is group therapy – a form of psychotherapy that involves one or more therapists working with several people at the same time.

In addition to group therapy, decompression treatment, which emphasizes ways in which positive reinforcement can shape and improve behavior, has been successful in reducing recidivism rates among violent juvenile offenders (Caldwell et al., 2001).

Despite there not being many surefire treatment methods for psychopaths, this does not mean they can’t be rehabilitated.

Famous Psychopaths

The behavior of psychopaths so often deviates from what is considered to be the norm, making us fascinated by these individuals. Fictionalized psychopaths are common protagonists in film and television, and real psychopaths often make national headlines when they act in dangerous and brutal ways as a result of their disorder.

One of the most famous psychopaths is Ted Bundy, who raped and murdered at least 36 women over the course of four years in the 1970s. But he wasn’t just a psychopath because of his violent crimes.

Not all psychopaths are heartless killers, and not all heartless killers are psychopaths. What distinguishes Bundy from others is his mask of sanity.

That is, on the surface, he appeared to be a charming and charismatic individual who people respected and trusted, but underneath that mask was a cold-hearted killer.

Bundy also carried out his horrific murders without any empathy or remorse, clear marks of psychopathy. Additionally, he admitted to meticulously plotting the gruesome crimes with little to no consideration for the suffering of his victims – the kind of “cold-heartedness” that is common in psychopaths (Hirschtritt et al., 2018).

Other household psychopaths are Jeffrey Dahmer, who murdered and dismembered 17 men and boys. Frank Abagnale Jr., who is considered one of the most prolific conmen in U.S. history. Tillie Klimek, a Polish serial killer, and Elizabeth Holmes, the mastermind behind one of the largest biotech scams in history.

Fictional psychopaths include Voldemort from Harry Potter, who has no regard for other people’s suffering; Patrick Bateman in American Psycho; and Villanelle in Killing Eve, who displays no empathy, guilt, or remorse for any of the murders she commits.

These famous psychopaths all exhibit characteristics that distinguish psychopaths from any other disorder, including that of ASPD. The next section will dive into what makes ASPD unique and how it differs from psychopathy.

What Is A Sociopath?

- Sociopathy is also referred to as antisocial personality disorder or ASPD.

- People with this disorder don’t follow society’s norms, are deceitful in personal relationships, and are inconsiderate of the rights of others.

- Sociopaths are highly impulsive, risk-taking, and violent.

- Unlike psychopathy, in which affective and interpersonal traits are paramount, behavioral traits alone make ASPD unique.

ASPD is not a short-term disorder – it is a longstanding pattern of behavior that impairs functioning and causes distress. ASPD has been studied by numerous psychologists and clinicians.

Research generally indicates a lifetime prevalence ranging from 1-4% of the general population, but, as with psychopathy, it is less likely among women (Lenzenweger et al., 2007).

Specifically, the lifetime prevalence in men is roughly 2-4%, whereas it ranges from 0.5-1% in women (Compton et al., 2005). Put differently, males are three to five times more likely to be diagnosed with ASPD than females (Trull et al., 2010).

The Origin of Antisocial Personality Disorder

ASPD does not have as robust a history as psychopathy. Beginning in the 1940s, Lee Nelken Robbins and Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck conducted separate studies on this disorder.

Their research revealed the continuity between childhood and adulthood behavioral problems, greatly influencing the diagnostic criteria for ASPD in the DSM-III.

Robins (1966) studied 524 subjects in a child guidance clinic between 1922 and 1932, with a follow-up in the 1950s. After analyzing her observations, Robins concluded that ASPD is a chronic and persistent disorder that does not remit. Ninety-four of the individuals Robins interviewed from the start met the diagnostic criteria for ASPD.

Similarly, the Gluecks (1950) followed 500 boys between the ages of 10 and 17 who were deemed officially delinquent by the Massachusetts correctional system.

The boys then participated in follow-up interviews at ages 25, 32, and 45 which revealed that antisocial behavior in childhood was strongly linked to adult criminality and deviant behavior.

The first version of the DSM, published in 1952, labeled this disorder as sociopathic personality disturbance, broken into four reactions: antisocial, dyssocial, sexual, and addiction.

The 1968 DSM-II listed antisocial personality as one of the ten personality disorders, but it wasn’t until the 1980 DSM-III that the full-term antisocial personality disorder was included.

The term is still included in the most recent version, the DSM-5, which is still used to diagnose ASPD today.

Etiology

As with most disorders, the biggest question is what causes this disorder. And similar to most answers, it is a combination of both genetic and environmental factors.

Although there isn’t overwhelming research that examines the heritability of ASPD, a study conducted by Qiang Fu and colleagues (2002) relied on an all-male Vietnam Era Twin Registry sample and observed that 69% of the variance was attributed to genetics and 31% of the variance was attributed to environmental influences.

In terms of genetics, evidence points toward the 2p12 region of a chromosome, variation within AVPR1A, and variation in the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) as having a role in the development of ASPD (Fragkaki et al., 2019).

But genetic mutations are generally not enough – these genes typically have to interact with the environment in order for the individual to actually exhibit signs of the disorder.

Research has revealed that environmental factors can range from adverse childhood experiences (both physical and sexual abuse) to childhood psychopathology (CD and ADHD; DeLisi et al., 2019).

Similar to psychopathy, the MAOA variant and reduced amygdala volume also play a role in making an individual more susceptible to ASPD (Raine, 2008). As demonstrated by these studies, both genes and the environment play a role in the age-old nature vs. nurture debate.

DSM-5 Diagnosis: The Major Signs and Symptoms

Unlike psychopathy, which has its own unique checklist for diagnosis, ASPD is diagnosed using the DSM-5, in addition to a psychological evaluation and an analysis of the patient’s personal and medical history.

The diagnostic criteria listed are as follows:

- A pervasive pattern of disregard for and violation of the rights of others since age 15 years, as indicated by three (or more) of the following:

- Failure to conform to social norms concerning lawful behaviors, such as performing acts that are grounds for arrest.

- Deceitfulness, repeated lying, use of aliases, or conning others for pleasure or personal profit.

- Impulsivity or failure to plan.

- Irritability and aggressiveness, often with physical fights or assaults.

- Reckless disregard for the safety of self or others.

- Consistent irresponsibility, failure to sustain consistent work behavior, or honor monetary obligations.

- Lack of remorse, being indifferent to or rationalizing having hurt, mistreated, or stolen from another person.

- The individual is at least age 18 years.

- Evidence of conduct disorder typically with onset before age 15 years.

- The occurrence of antisocial behavior is not exclusively during schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

Generally speaking, antisocial personality disorder is described as a pattern of socially irresponsible, exploitative, and guiltless behavior (Goodwin & Guze, 1989).

As the DSM indicates, the main symptoms include failure to conform to the law, failure to maintain consistent employment, manipulation, deception, and failure to develop stable interpersonal relationships (Black, 2015).

Additionally, even though this disorder is not diagnosed until an individual is 18 years old, a patient must have shown some evidence of conduct disorder (the ASPD equivalent for children) prior to being diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder (Black. 2015).

Treatment

Antisocial personality disorder is extremely difficult to treat, especially with severe symptoms. It is an extremely complex disorder and can manifest in very different ways depending on the individual.

Nevertheless, the literature suggests certain medications to treat co-occurring conditions. Specifically, aggressive behavior can be treated with second-generation antipsychotics, including risperidone and quetiapine.

Additionally, anticonvulsants, such as oxcarbazepine and carbamazepine, can be used to aid with impulsivity (Fisher & Hany, 2019).

Psychotherapy, or talk therapy, can also be used to treat ASPD. This approach might incorporate anger and violence management, treatment for alcohol and substance abuse, and treatment for other mental health conditions (“Antisocial Personality Disorder,” 2019).

The least costly and most effective approach, however, is early treatment intervention with conduct disorder in children (Frick, 2016). Treating ASPD is as complex as the disorder itself is, but research into medication and therapy is certainly promising.

Empirical Research

Treatment is not the only domain in which there is research on ASPD. There is an abundance of empirical literature on this disorder revealing its comorbidity, prevalence, risk factors, and more.

Notably, one study found that between the ages of 5 and adolescence, males manifest more externalizing symptoms than females, whereas females manifest more internalizing symptoms than males.

However, this sex difference weakens with adolescence. Nevertheless, boys and girls do exhibit different types of antisocial behaviors and aggression, and these differences do extend to adulthood (Cale & Lilienfeld, 2002).

Another study that observed types of behavior among a younger population looked into the different forms of conduct disorder (CD) that might predict future risk for ASPD in women.

The researchers found that the types of CD, such as interpersonal and physical aggression vs. destruction of property vs. the traditional diagnosis, rather than the number of behaviors, is a more important indicator for identifying women who might be at risk (Burnette & Newman, 2005).

Work done by Morizot and Kazemian (2014) found that individuals who have a lower IQ are at a higher risk for ASPD.

And not surprisingly, due to the impulsive nature of ASPD, another study found that substance use disorders are the most highly comorbid conditions with ASPD.

The National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, a large household survey conducted in the U.S., reported that those with ASPD were 7 to 8 times more likely to meet the criteria for alcohol dependence, 15 to 17 times more likely to meet the criteria for drug dependence, and 5 to 6 times more likely to be nicotine dependent compared to those without ASPD (Trull et al., 2010).

These are only a few of the many studies that help us understand this extremely complicated disorder, and scholars continue to do research on ASPD every day.

Famous Sociopaths

There are many famous sociopaths, both real and fictional, but two of the most notorious examples are Diane Downs and Alex DeLarge. Downs, a rare female sociopath, murdered her daughter and attempted to kill her two other children.

This violent aggression, coupled with Downs’ decision to lie to the police and claim that a man had attempted to carjack her and shoot the children, are key indicators of ASPD.

Downs was convicted in 1984 and sentenced to life in prison, and she has since been diagnosed with narcissistic, histrionic, and antisocial personality disorders (Payne & Hopper, 1998).

On the fictional side, Alex DeLarge, the protagonist of the film A Clockwork Orange, which was based on Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel of the same name, is another well-known sociopath.

Alex engages in persistent criminal activity, assaulting and murdering numerous innocent people. And after a short stay in prison, he is committed to a mental hospital to undergo rehabilitative treatment (Sandi, 2016).

Alex’s actions demonstrate clear moral depravity, and he has no sense of shame when he carries out these brutal acts. He consistently fails to obey the law, has a strong drug addiction, and also has defective social relationships.

He is manipulative, deceptive, and impulsive, and at the beginning of the story, Alex is only 15 years old, meeting the ASPD requirement that the individual exhibit signs of CD before an official diagnosis at 18 years or older. Alex DeLarge is a textbook sociopath.

What Are Personality Disorders?

In psychological terms, personality is defined as the way of thinking, feeling, and behaving that makes you unique and distinguishes you from others.

Your genetics, environment, and experiences affect your personality, and unlike temporary moods or emotions, personality typically stays relatively stable over the course of your lifetime (Robitz, 2018).

An individual is diagnosed with a personality disorder when their thoughts, feelings, and behavioral patterns deviate from cultural norms and expectations, cause distress or significant problems functioning in society, and persist over a long period of time (American Psychological Association, 2013).

Typically, personality disorders affect the way you think about yourself and others, the way you respond emotionally, the way you relate to other people, and the way you control your behavior.

Some examples of personality disorders are borderline personality disorder and narcissistic personality disorder. This article, however, will focus on two specific personality disorders: psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder.

Although both only affect a tiny percentage of the population, ASPD and psychopathy are frequently depicted in film and television. Additionally, violence can be a consequence of these disorders, so gruesome acts of murder and abuse often make national news headlines.

Because these disorders are often depicted on the big screen and on the news, and because they manifest in similar ways, they are often conflated and confused with one another.

However, it is important to understand that these are two distinct disorders, each with separate symptoms and diagnostic criteria, so as to avoid mislabeling an individual.

Broadly speaking, a diagnosis of sociopathy (ASPD) is based on an individual’s behavior, whereas psychopathy includes an interpersonal and affective dimension.

A common way of distinguishing between the two is describing an individual with ASPD as “hot-headed” – this person has a quick temper and acts in impulsive and erratic ways – and an individual with psychopathy as “cold-hearted” – this person is calculating and lacks any empathy or emotion.

Further Reading

References

Aharoni, E., Sinnott-Armstrong, W., & Kiehl, K. A. (2012). Can psychopathic offenders discern moral wrongs A new look at the moral/conventional distinction. Journal of abnormal psychology, 121(2), 484.

American Psychiatric Association. (1952). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5.

Antisocial personality disorder. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/antisocial-personality-disorder/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353934

Baskin-Sommers, A., Stuppy-Sullivan, A. M., & Buckholtz, J. W. (2016). Psychopathic individuals exhibit but do not avoid regret during counterfactual decision making. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(50), 14438-14443.

Black, D. W. (2015). The natural history of antisocial personality disorder. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 60(7), 309-314.

Burnette, M. L., & Newman, D. L. (2005). The natural history of conduct disorder symptoms in female inmates: On the predictive utility of the syndrome in severely antisocial women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(3), 421-430.

Caldwell, M. F., & Van Rybroek, G. J. (2001). Efficacy of a decompression treatment model in the clinical management of violent juvenile offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 45(4), 469-477.

Cale, E. M., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2002). Sex differences in psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder: A review and integration. Clinical psychology review, 22(8), 1179-1207.

Cleckley, H. M. (1951). The mask of sanity. Postgraduate medicine, 9(3), 193-197.

Compton, W. M., Conway, K. P., Stinson, F. S., Colliver, J. D., & Grant, B. F. (2005). Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of DSM-IV antisocial personality syndromes and alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(6), 677-685.

DeLisi, M., Drury, A. J., & Elbert, M. J. (2019). The etiology of antisocial personality disorder: The differential roles of adverse childhood experiences and childhood psychopathology. Comprehensive psychiatry, 92, 1-6.

Fisher, K. A., & Hany, M. (2019). Antisocial Personality Disorder.

Forth, A. E. (2005). Hare psychopathy checklist: Youth version. Mental health screening and assessment in juvenile justice, 9, 324-338.

Fragkaki, I., Cima, M., Verhagen, M., Maciejewski, D. F., Boks, M. P., Van Lier, P. A., … & Meeus, W. H. (2019). Oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) and deviant peer affiliation: a gene–environment interaction in adolescent antisocial behavior. Journal of youth and adolescence, 48(1), 86-101.

Frick, P. J. (2016). Early identification and treatment of antisocial behavior. Pediatric Clinics, 63(5), 861-871.

Fu, Q., Heath, A. C., Bucholz, K. K., Nelson, E., Goldberg, J., Lyons, M. J., … & Eisen, S. A. (2002). Shared genetic risk of major depression, alcohol dependence, and marijuana dependence: contribution of antisocial personality disorder in men. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(12), 1125-1132.

Gao, Y., & Raine, A. (2010). Successful and unsuccessful psychopaths: A neurobiological model. Behavioral sciences & the law, 28(2), 194-210.

Glenn, A. L., Yang, Y., & Raine, A. (2012). Neuroimaging in psychopathy and antisocial personality disorder: Functional significance and a neurodevelopmental hypothesis.

Glueck, Sheldon, and Eleanor Glueck. “Unraveling juvenile delinquency.” Juv. Ct. Judges J. 2 (1950): 32.

Goodwin, D., & Guze, S. B. (1989). Sociopathy (antisocial personality). In Psychiatric diagnosis (pp. 209-225). Oxford University Press.

Grann, M. (2000). The PCL–R and gender. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 16(3), 147.

Guggenbühl-Craig, A. (1999). The emptied soul: On the nature of the psychopath (GV Hartman, Trans.). Woodstock, CT: Spring.(Original work published 1980).

Hare, R. D. (1980). A research scale for the assessment of psychopathy in criminal populations. Personality and individual differences, 1(2), 111-119.

Hare, R. D. (2003). The psychopathy checklist–Revised. Toronto, ON, 412.

Henderson, D. K. (1942). Psychopathic states. Journal of Mental Science, 88(373), 485-490.

Hervé, H. (2007). Psychopathy across the ages: A history of the Hare psychopath. The psychopath: Theory, research, and practice, 31-55.

Hirschtritt, M. E., Carroll, J. D., & Ross, D. A. (2018). Using Neuroscience to Make Sense of Psychopathy. Biological psychiatry, 84(9), e61-e63.

Kegan, R. (1986). The child behind the mask: Sociopathy as developmental delay. Unmasking the psychopath. New York: Nor

Kiehl, K. A., & Hoffman, M. B. (2011). The criminal psychopath: History, neuroscience, treatment, and economics. Jurimetrics, 51, 355.

Lenzenweger, M. F., Lane, M. C., Loranger, A. W., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological psychiatry, 62(6), 553-564.

Mathieu, C., Neumann, C. S., Hare, R. D., & Babiak, P. (2014). A dark side of leadership: Corporate psychopathy and its influence on employee well-being and job satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 59, 83-88.

Millon, T., Simonsen, E., & Birket-Smith, M. (1998). Historical conceptions of psychopathy in the United States and Europe. Psychopathy: Antisocial, criminal, and violent behavior, 3-31

Payne, S. H., & Hopper, D. (1998). Mental disorders in film. American History, 10(1998).

Prichard, J. C. (1837). A treatise on insanity and other disorders affecting the mind (Vol. 1837). Haswell, Barrington, and Haswell.

Raine, A. (2008). From genes to brain to antisocial behavior. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(5), 323-328.

Robins, L. N. (1966). Deviant Children Grown Up, A Sociological and Psychiatric Study of Sociopathic Personality.

Robitz, R. (2018). What are personality disorders? Retrieved from https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/personality-disorders/what-are-personality-disorders

Salekin, R. T., Rogers, R., & Sewell, K. W. (1997). Construct validity of psychopathy in a female offender sample: A multitrait–multimethod evaluation. Journal of abnormal psychology, 106(4), 576.

Sandi, A. E. (2016). The Anti-Social Symptoms Seen in Alex Delarge’s Characteristics in A Clockwork Orange By Anthony Burgess (Doctoral Dissertation, Sanata Dharma University).

Trull, T. J., Jahng, S., Tomko, R. L., Wood, P. K., & Sher, K. J. (2010). Revised NESARC personality disorder diagnoses: gender, prevalence, and comorbidity with substance dependence disorders. Journal of personality disorders, 24(4), 412-426.

Wynn, R., Høiseth, M. H., & Pettersen, G. (2012). Psychopathy in women: theoretical and clinical perspectives. International journal of women’s health, 4, 257.